Vital lessons you likely didn’t learn in school.

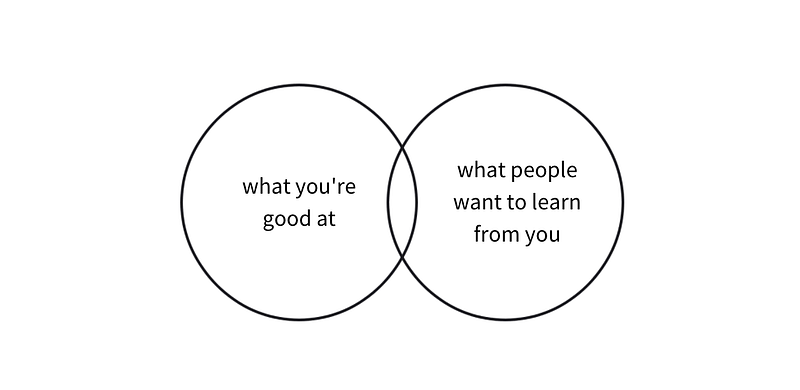

Learning how to learn is the meta-skill that accelerates everything else you do.

Once you understand the fundamentals of learning science, you can save hours every time you learn something new. You become more strategic in approaching new subjects and skills instead of relying on often ineffective learning methods many pick up in school.

I love the science of learning, an interdisciplinary domain that builds on cognitive science, educational psychology, computer science, anthropology, and more. I can spend hours learning about how our brains absorb and retain information (here is a list of the recent books I’ve read).

Below are key insights I’ve learned about how we learn. Every single one will help you understand how your brain learns. By doing so, you’ll make better decisions on your journey to wisdom.

#1 Unlearn this common learning myth

You don’t learn better when you receive information in your preferred learning style (e.g., auditory, visual, kinesthetic). There is no evidence from controlled experiments that suggests teaching in a person’s preferred learning style will help them learn.

“Brain imaging shows that we all rely on very similar brain circuits and learning rules. The brain circuits for reading and mathematics are the same in each of us, give or take a few millimeters-even in blind children. We all face similar hurdles in learning, and the same teaching methods can surmount them. Individual differences, when they exist, lie more in children’s extant knowledge, motivation, and the rate at which they learn.”

— Stanislas Dehaene in “How We Learn”

#2 Forgetting is not your personal flaw

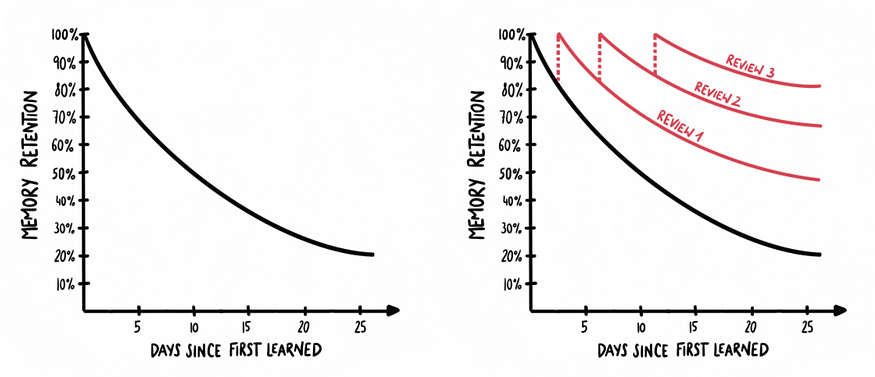

I always thought forgetting was a character’s flaw. But it isn’t. Forgetting is no error in an otherwise functional memory system. While science is not clear yet about the exact rate of forgetting, there’s a consensus that your ability to recall things from memory decreases over time. The most effective learning strategies interrupt the process of forgetting.

For example, spaced repetition, which allows some forgetting to occur between your learning sessions, strengthens both the learning and your capability to use the routes and cues for retrieving that piece of knowledge.

“Spacing out your practice feels less productive for the very reason that some forgetting has set in and you’ve got to work harder to recall the concept. What you don’t sense in the moment is that this added effort is making the learning stronger.”

— Brown et al. in “Make it Stick”

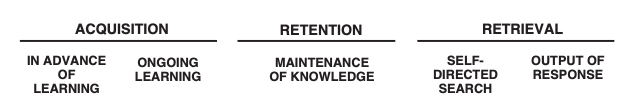

#3 Human memory works in these three stages

In the acquisition phase, you link new information to existing knowledge; in the retention phase, you store it; and in the retrieval phase, you get information out of your memory.

Storage and retrieval strength are two factors that determine whether you’re able to remember and recall what you learn. Storage strength shows how associated or “entrenched” it is with everything else in one’s memory. The retrieval strength of an item in your memory determines how easily you can access it.

“Current retrieval strength is assumed to determine completely the probability that an item can be recalled, whereas storage strength acts as a latent variable that retards the loss or enhances the gain of retrieval strength.”

— Brown et al. in “Make it Stick”

#4 Move things from your short-term to your long-term memory

Your working memory is limited, but schemas stored in your long-term memory aren’t. So the goal of learning is to move things from working memory into your long-term memory.

Several methods have received robust support from decades of research. Below are two highly effective ways to make learning deeper and more durable:

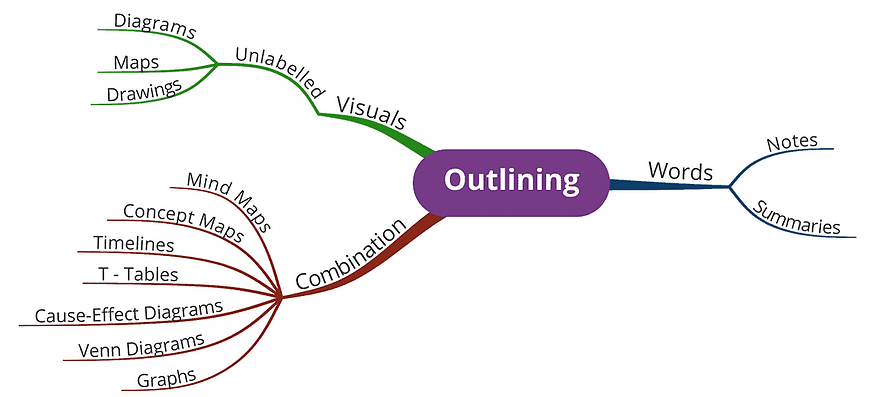

- Elaboration. When you elaborate, you explain and describe an idea in your own words. Thereby you connect and relate the new material to what you already know (=more meaningful encoding).

- Dual coding. Using visual and verbal cues, you can more effectively keep information in your long-term memory. The next time you try to remember information, attach an image or picture to visualize it.

The more details and the stronger you connect new knowledge to what you already know, the better because you’ll be generating more cues. And the more cues they have, the easier you can retrieve your knowledge.

#5 Focus on these two factors for meaningful practice

Repetition by itself does not lead to good long-term memory.

Practice doesn’t make perfect.

Practice makes permanent.

You can repeat a specific behaviour indefinitely without getting better at it. All you do is manifest the existing technique. It depends on how you learn and practice.

One thing that helps is adding variability to your learning. Work with different teachers, peers, and styles. Mix up your problems.

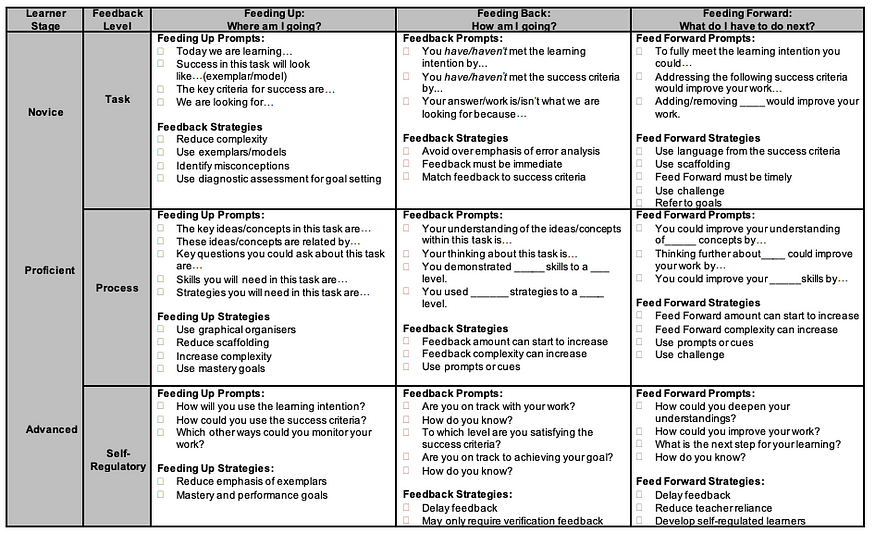

The second thing you want to include is feedback. To improve, you need to know what exactly you’re striving for and become aware of your shortcomings. Feedback helps you manifest the correct revisions rather than repeating ineffective behaviour.

“Purposeful practice involves feedback. Without feedback— either from yourself or from outside observers — you cannot figure out what you need to improve on or how close you are to achieving your goals.”

— Ericsson and Pool in “Peak: Secrets from the New Science of Expertise”

#6 The reason why learning needs repetition

In the past decades, neuroscientists argued neurons in gray matter would be a key factor for learning. But more recently, neuroscientists revisited this assumption. They used magnetic resonance imaging to observe the brain’s structure while learning.

Below the gray matter surface lies the white matter. It’s white because it contains billions of axons coated with a fatty substance called myelin.

Myelin is a critical factor for learning as it determines your brain’s information transmission speed. Myelin makes signals faster, stronger, and more precise.

Every time you repeat a practice, the myelin layer thickens. The more you practice a specific skill, the better insulated the circuit becomes. In return, your thoughts and behaviour become faster and more precise.

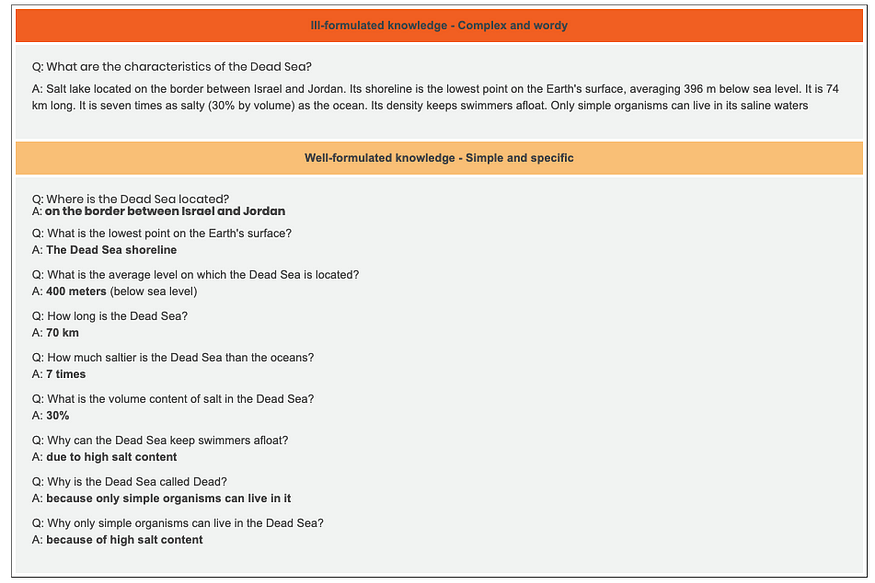

#7 Don’t reread a book or a presentation but test yourself

When it comes to learning, don’t trust your intuition — it can lead you to pick the wrong learning strategies. While rereading feels efficient, it is less effective than retrieving (trying to recall something from your memory).

When you practice retrieval, you withdraw learned information from your long-term memory into your working memory. While this requires effort (and increases germane cognitive load), it directly improves your memory, transfer, and inferences.

“Mastering the lecture or the text is not the same as mastering the ideas behind them. However, repeated reading provides the illusion of mastery of the underlying ideas. Don’t let yourself be fooled.”

— Brown et al. in “Make it Stick”

#8 For optimal learning, use both of your brain modes

For effective learning, you need your brain’s focused and diffused mode.

In focused mode, you think based on prior knowledge and rely on often-used neural connections associated with problem-solving on familiar tasks.

The diffused mode, on the other hand, feels like daydreaming and enables unpredictable, new neural connections.

Many people optimize their days for focused mode thinking — through deep work, flow states, and other work sessions. Learning can happen during focused attention.

But the diffused mode is equally important. Diffused thinking only occurs when our minds can wander, for example, during a shower or while going for a walk. While this feels like taking a brain break, our mind continues to work for us.

To integrate the two thinking modes into your daily schedule (and to beat procrastination), you can use the Pomodoro technique — focusing for 25 minutes and giving yourself a pleasurable 5-minute brain break afterwards.

“Learn a new skill in short blocks of around 20 minutes followed by short rest periods. Why? Because mind wandering will occur after 15 to 20 minutes. This finding calls for professional moderation of any event at which people participate. Skill development involves periods of growth followed by periods of consolidation or even lack of growth.”

— Hattie and Yates in “Visible Learning and the Science of How We Learn”

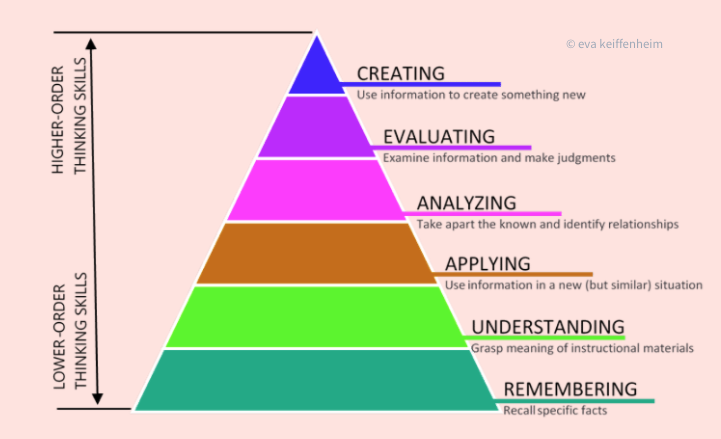

#9 Fact-learning is essential for mastering “21st-century skills”

Declarative knowledge (such as facts) is needed for procedural knowledge (such as skills). It’s not either facts or skills. You need both.

If you don’t memorize facts to encode them into your long-term memory, you’ll never have the same processing fluency and thought quality as someone who has. It’s as if you’re trying to win a race walking barefoot while the other person sits on an e-bike.

Your long-term memories can store thousands of facts that form a schema. This schema helps you learn new facts about that topic and is the foundation for conceptual understanding. While you’re problem-solving, you have more working memory capacity available because a lot is stored in your long-term memory.

The benefit of remembering information is not in the knowledge itself but in the way you can deploy it. You build a mental structure that helps you develop new thoughts and knowledge through memorization.

When solving problems, thinking critically, or generating new ideas, you don’t rely on your limited working memory capacity but on your basically unlimited long-term memory.

“Our long-term memory does not have the same limitations as working memory. It is capable of storing thousands of pieces of information. This allows us to cheat the limitations of working memory in lots of ways.”

— Daisy Christodoulou

#10 Your brain’s capacity is basically unlimited

There’s no such thing as a full brain. What can feel like juggling too many pieces at a time is a high cognitive load on your working memory.

Your long-term memory capacity is unlimited — and the more you learn, the more possible connections you create for future learning, which makes additional learning easier. There’s no limit to how much you can remember as long as you relate it to what you already know.

“It is far easier to build on existing knowledge than it is to learn new material from scratch. New information, which cannot be related to existing knowledge, is quickly shed.”

— Hattie and Yates in “Visible Learning and the Science of How We Learn”

#11 Pay attention to attention

Attention is the gateway to learning: you can’t remember any information if it hasn’t been amplified by attention and awareness. Become a master at directing your attention to what matters.

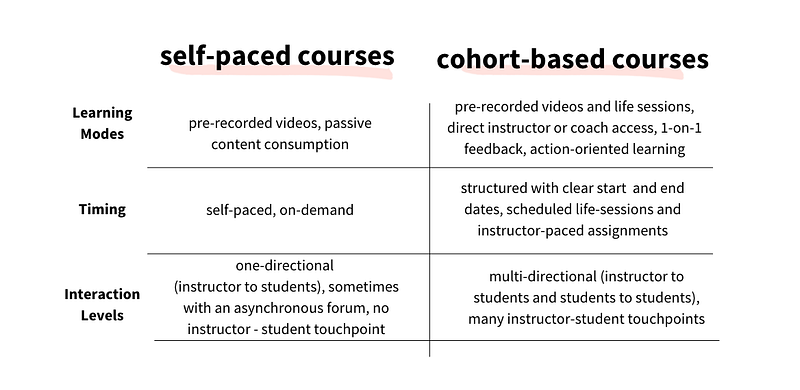

#12 Active learning always trumps passive learning

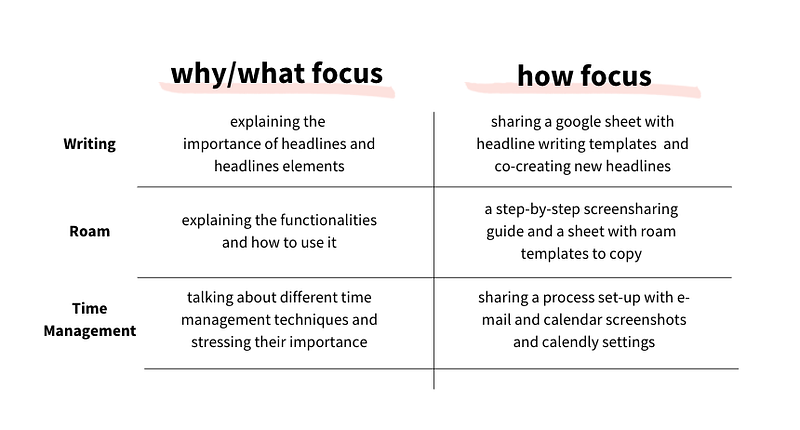

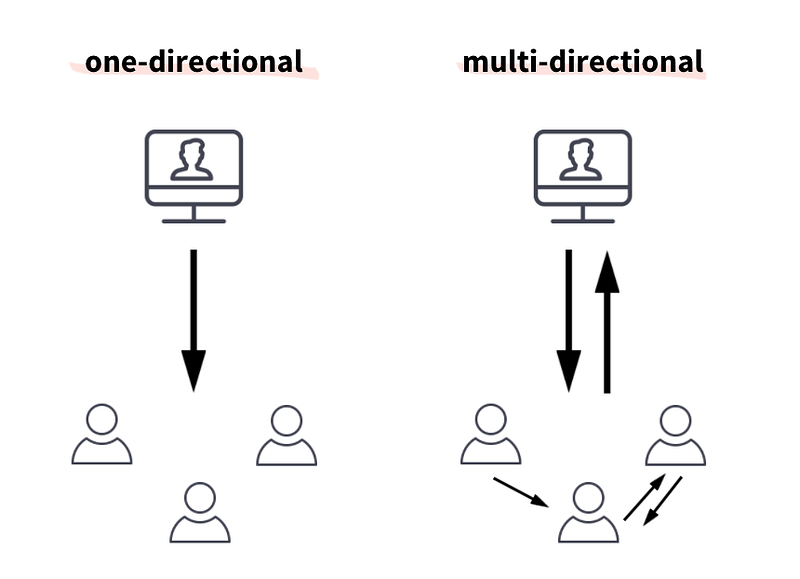

Learning does not occur passively through simple exposure to data or lectures. Ideally, you are active, curious, engaged, and autonomous in your learning.

You learn best when you’re focused and engaged through questions, reflection, or discussions (rather than passively listening to lectures or watching videos).

“Growing bodies of research and practice, from early childhood to university classrooms and beyond, demonstrate the benefits of moving beyond traditional lecture-driven approaches in favor of ‘active learning.’”

— Hirsh-Pasek et al. quoting Yannier et al. in “Making Schools Work: Bringing the Science of Learning to Joyful Classroom Practice”

#13 Set yourself a learning objective

You learn best when the purpose of learning is explicitly stated. Before you dive into practising, consider which goal you want to achieve. Set clear learning objectives for yourself.

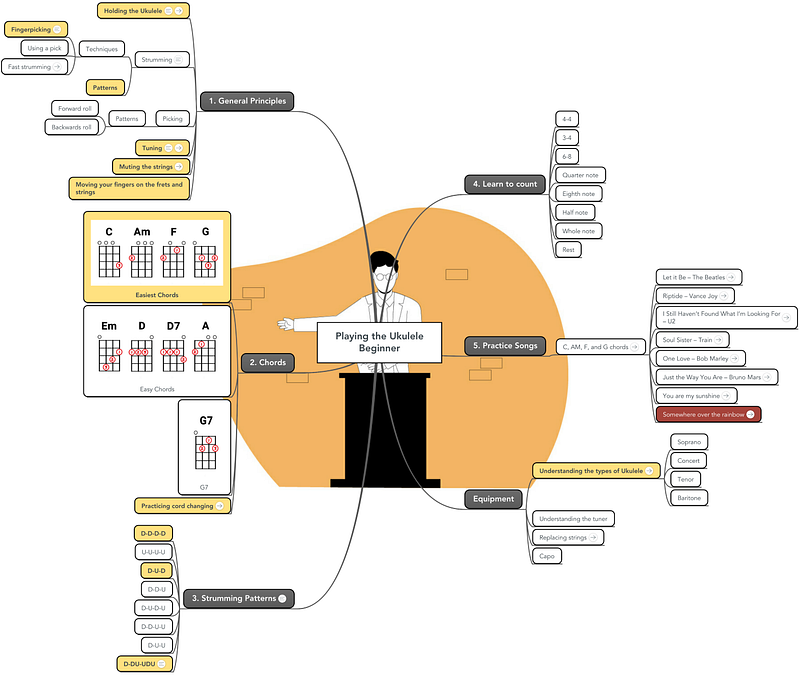

Break down your ultimate goal into sub-steps. Instead of saying you want to become better at playing the guitar, focus on one specific part of it, e.g., learning three new strumming patterns or five new chords. One clear outcome is a thousand times better than overarching terms such as “succeed” or “get better.”

#14 Eliminate any distractions that distort your focus.

How easy you find learning something depends on your cognitive load. And while you can’t influence the intrinsic cognitive load (= the difficulty of the subject you want to master), you can optimize for extraneous cognitive load — by using great instructional design and minimizing any distractions.

When working on hard tasks, remove triggers towards other tasks. For example, close your tabs and e-mails, and put your phone on flight mode.

#15 Appreciate your progress rather than talking yourself down

Feeling appreciated and the awareness of your progress are rewarded in and of themselves. Let go of anxiety and stress as much as possible and focus on your effort and progress. Low emotions crush your brain’s learning potential, whereas providing the brain with an encouraging environment may reopen the gates of neuronal plasticity.

Want to feel inspired and become more thoughtful about how you learn?

Subscribe free to my Learn Letter. Each Wednesday, you’ll get proven tools and resources that elevate your love for learning. I’ll share my Top 10 All-Time Articles immediately as a thank you.