While they won’t make you smarter, you can still use them to your advantage.

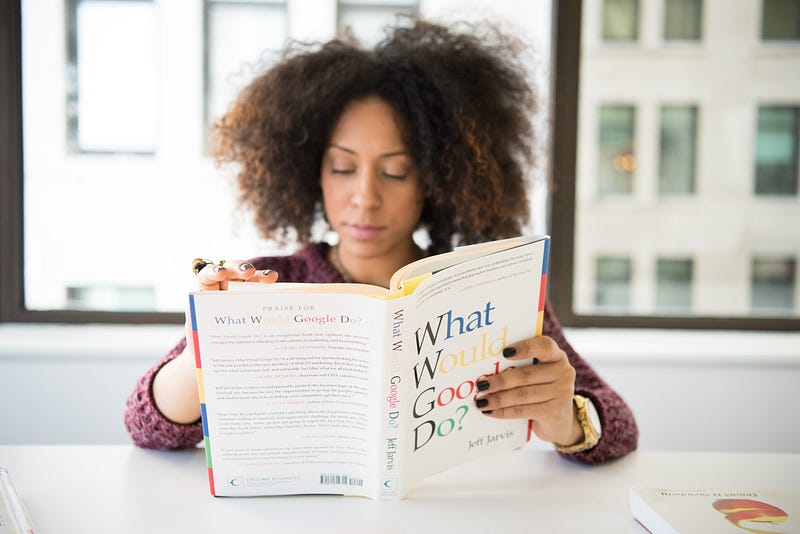

Because I read a book a week, people often ask me why I don’t use Blinkist instead.

Blinkist is a book summary service, similar to Shortform and getabstract. You find the key ideas of non-fiction books.

The tempting promise — you will gain more knowledge in less time.

While this is flawed for various reasons (e.g. because brains don’t work like recording devices and you don’t acquire knowledge by reading sentences), book summary services have even more strikes against them:

- No cross-checking. When you read through summaries, you can’t check the quality of the book’s sources in its appendix. You won’t be able to judge whether books are light on the science and heavy on the anecdotal evidence part.

- Additional subjective filters. Instead of you, the summary author picks what’s most relevant. You will never know whether you might have found other passages to be way more relevant than Blinkist’s selection.

- Lack of complexity and context. It’s in the essence of summaries to compromise on depth and meaning. You’ll get the author’s conclusion without understanding their reasoning. Blinkist “eliminates the fluff” — but often, the fluff is what will invite you to deeper reflections and questions.

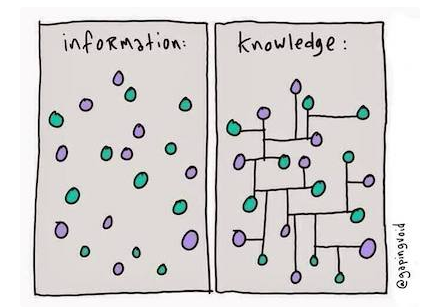

And while summaries often feel like a pale ghost of the real book, there is still a very valid use case for them. To understand this, let’s quickly recap the following concept.

Adler’s Four Levels of Reading

Mortimer J. Adler, an American philosopher and one of the brightest readers of the 20th century. In ‘How to Read a Book’, he explains the four reading levels.

Before I learned about these levels, precisely level two, I was among the people who’d dive straight into a book. I wouldn’t bother to read the table of contents or the preface. I started to read from front to back, unknowingly wasting a lot of time.

Basic Reader (Level 1)

If you can read and understand words you’ve mastered this level already.

Strategic Reader (Level 2)

Think of this as a quick chat you have with the author to determine whether you should read the entire book, a few chapters, or nothing at all.

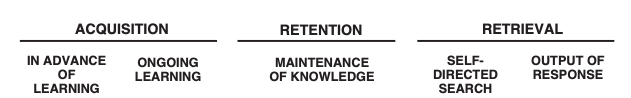

Critical Reader (Level 3)

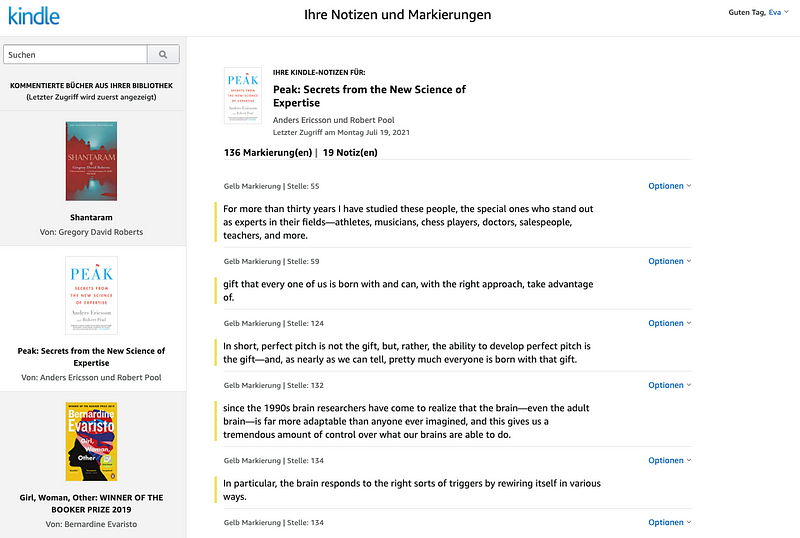

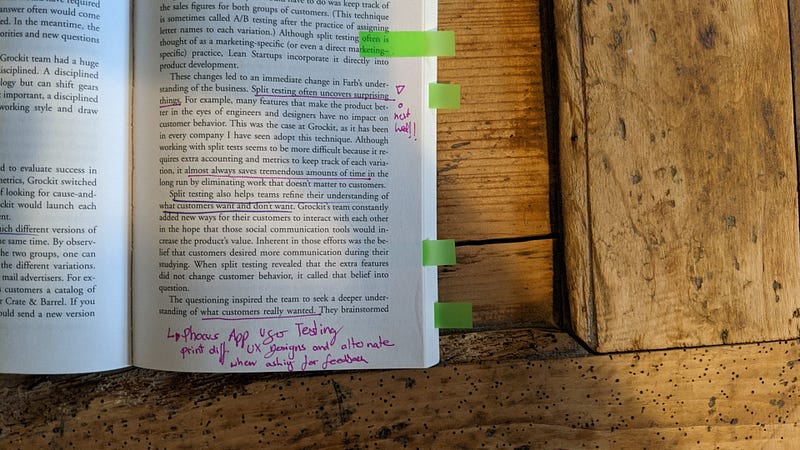

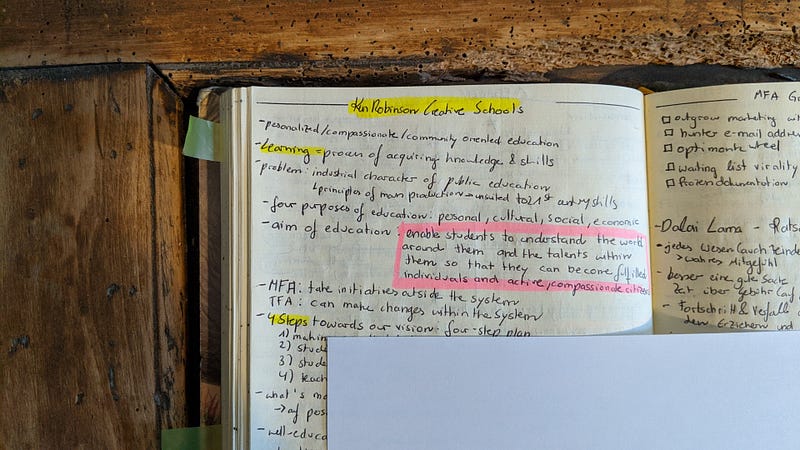

Effortless reading is like writing in the sand, here today and gone tomorrow. Reading a book is not the same as mastering the ideas behind it. Adler suggests you should take notes and answer questions while you read. What is the book about as a whole? What is being said in detail, and how? Is the book true, in whole or in part?

Synoptical Reader (Level 4)

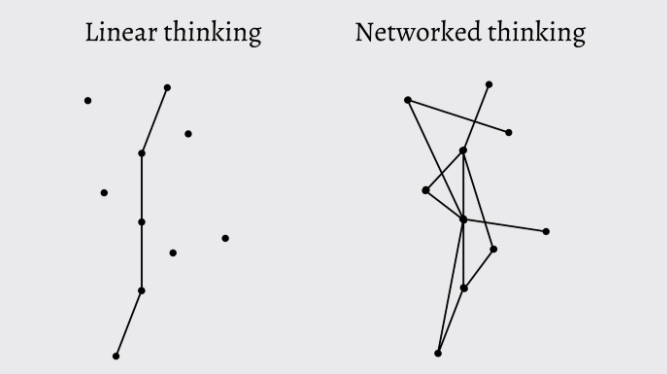

This level is about relating different books on the same topic to master it fully. By deploying syntopical reading, you can compare the author’s arguments, explore research questions and draw a knowledge map.

“With the help of the books read, the syntopical reader is able to construct an analysis of the subject that may not be in any of the books. It is obvious, therefore, that syntopical reading is the most active and effortful kind of reading.“

How Blinkist Can Help You Become a Strategic Reader

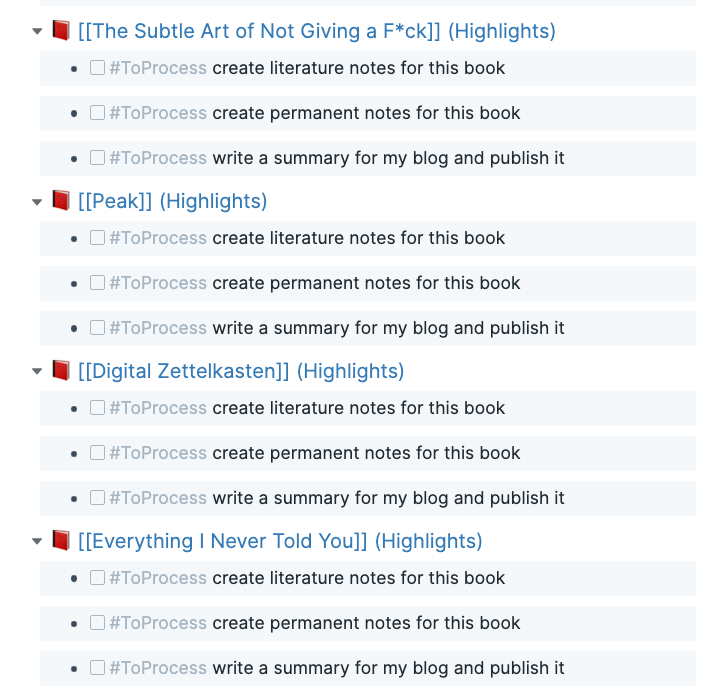

Summary services support you in making an informed decision before investing time in reading.

Before I used the software, I set myself a time limit of 20 minutes and completed the following three steps for every time-intense non-fiction book I planned to read:

- Looking at the cover and skim the preface to get a feeling for the book’s category.

- Reading the table of contents to identify the most relevant chapters.

- Identifying the main points by reading a paragraph or a whole page and figuring out if I want to read the book.

Now, this is where Blinkist can help you. Instead of doing the steps yourself, you can quickly browse through a couple of books within the same category.

By reading through the main points, you feel whether the book is worthy of your time.

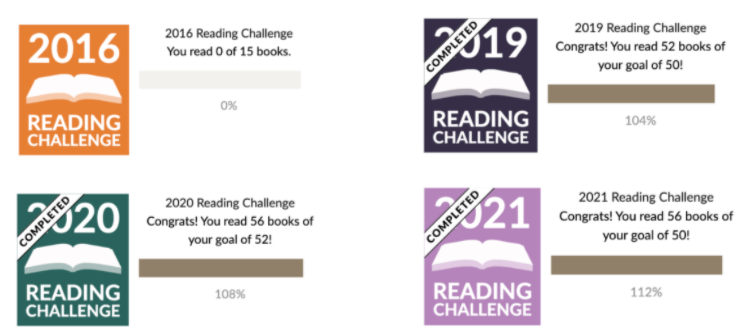

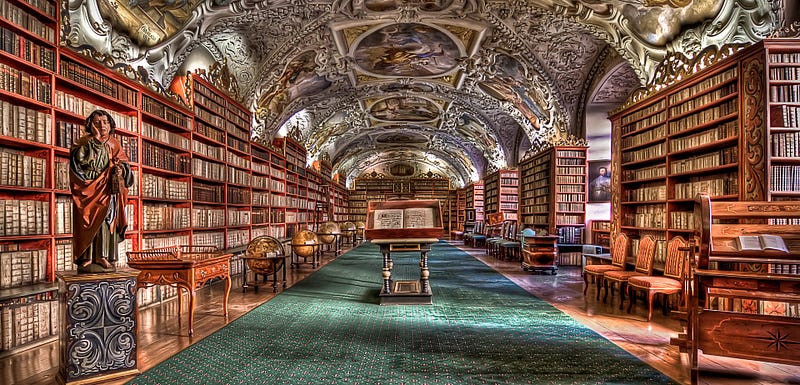

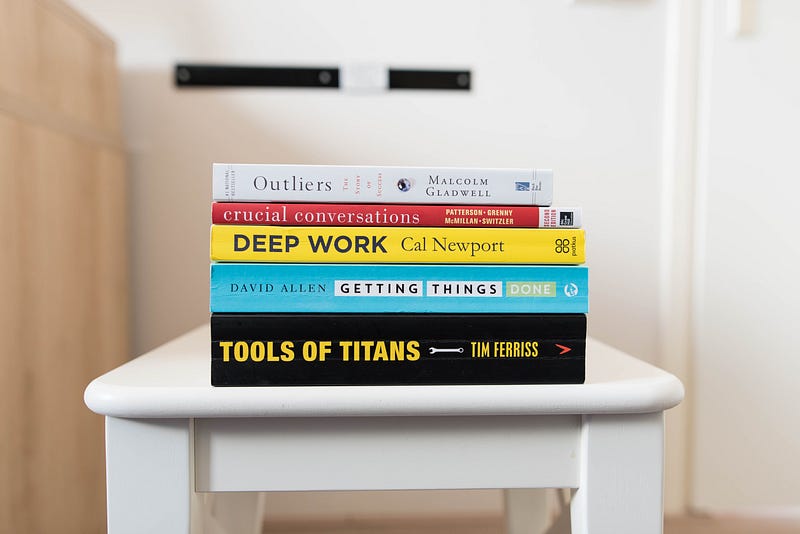

New books are written and published every minute. Yet, you only have a limited number of books you can read in your life.

Not all books are created equal, and most books aren’t worth your time. But some books do have the power to change your life for the better.

Using summary services as a tool to identify them can help you on your path to health, wealth and wisdom.

“In the case of good books, the point is not to see how many of them you can get through, but rather how many can get through to you.”