A quick guide that helps you find the worthy ones.

This year I spent around $5000 on online courses.

Warren Buffet said, “the best investment you can make is an investment in yourself. The more you learn, the more you’ll earn.”

But his statement is flawed.

Not all learning investments are created equal. People who’ve excelled at their craft are often not the best teachers. Likewise, creators who write the best sales copy don’t offer the most value.

Here’s precisely how you can spot bad online courses so that you won’t waste your time and money.

1) They Tell But Don’t Show

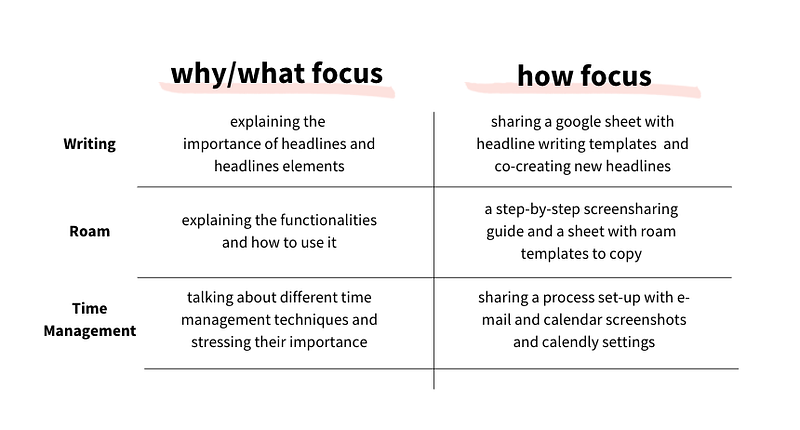

Most online courses are useless because they focus on the why and what instead of the how.

In a Medium writer’s online course, for example, the instructors spend 90% of the time exploring what writing consists of. They have an hour-long conversation about the importance of consistency. Yet, they don’t show the students how they can write consistently.

The medium star could’ve talked about the roadblocks and how he overcame them. He could’ve shared his calendar or accountability system. He could’ve shared strategies for when you’re struggling to get started. But he didn’t. For me, the course felt like a time-waster.

“Never tell us a thing if you can show us, instead.”

What to look out for instead:

Look for how material instead of endless talks on the why and what. Valuable things often include templates, tutorials, spreadsheets, and screen-sharings.

Here are some examples, so you know how to tell the difference:

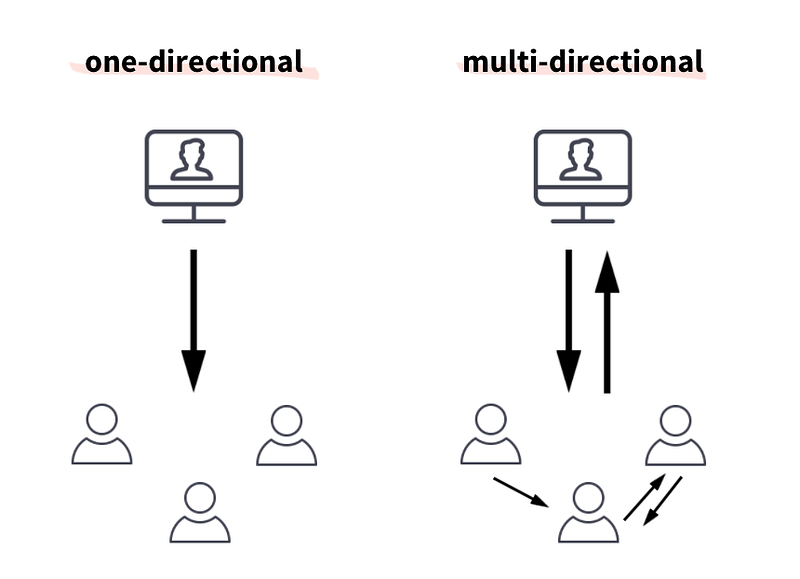

2) Instructors Teach in One Direction

“Active learning works, and social learning works,” said Anant Agarwal, founder and chief executive of edX, in an interview with the New York Times. To back this up, a recent study suggests social learning helps you complete online courses.

Yet, most online course creators choose alow-maintenance model. They pre-record videos so you can watch them at your own pace.

But what’s scalable for the instructors isn’t the best for you. Data from Harvard University and MIT shows only three to four percent complete self-paced online courses.

To increase your chances of success, you need a community.

I love Cam Houser’s comment in a joint Slack channel: “People don’t take courses for information. That’s what google and youtube are for. They take courses for outcomes, accountability, process, community.”

What to look out for instead:

A slack channel or Facebook group isn’t enough. Great courses offer structured space for social learning. You have an accountability group, comment on each other’s work, and have regular live touchpoints with your instructors or coaches.

3) They Ignore the Principle of Directness

Online courses are often distant from the actual application. You watch videos about your desired skill, but you never actually practice.

Let’s consider one of my favorite examples.

Imagine you’re a frequent flier. Before every start, you watch the video of a flight attendant putting on the life vest. You watch the video again and again.

But as this study shows, actually putting on the inflatable life vest a single time would be more valuable than repeatedly watching another person doing it. You acquire true mastery by performing the procedure yourself.

The author of ‘Ultralearning’ calls this principle directness. It is essential for mastering any skill. Yet, most online courses teach skills far from direct.

What to look out for instead:

You don’t learn by watching things. You learn by doing them. So the more you engage with the content, the likelier it will stick with you.

What’s your desired outcome behind taking the course? Check whether you have assignments that are directly linked to your desired skill. Pick a class as close to your end goal as possible.

If you take a course on e-mail newsletters, write your e-mail and ask for feedback. If you take a drawing class, do your first drawing. If you take a course on online writing, write your first article.

Just like the minimum viable product, find a minimum viable action. What is the simplest thing you can do based on what you’ve just learned?

Foster a bias towards action. You learn best when you do the work.

“Just keep working at it, and you’ll get there is wrong. The right sort of practice carried out over a sufficient period of time leads to improvement. Nothing else.”

— Anders Ericsson

4) They Don’t Understand the Science of Learning

Masters might not be the best teachers. More likely, they’re beginners when it comes to instructional design and the science of learning.

Most online courses are built on the assumption that our brains work like recording devices. But students don’t acquire their desired skills by consuming content. Instead, learning is at least a three-step process — we acquire, encode, and retrieve.

Learning scientist Roediger writes: “Learning that’s easy is like writing in sand, here today and gone tomorrow. Learning is deeper and more durable when it’s effortful.”

Learning through passive content consumption isn’t effortful. That’s why most online courses are a mere form of entertainment.

What to look out for instead:

Look out for active learning elements. Check whether the course uses evidence-based learning strategies such as:

- retrieval practice ⇾ recall something you’ve learned in the past from your memory

- spaced repetition ⇾ repeat the same piece of information across increasing intervals

- interleaving ⇾ alternating before each practice is complete

- elaboration ⇾ rephrasing new knowledge and connecting it with existing insights

- reflection ⇾ synthesize, abstract, and articulate key lessons taught by experience

- self-testing & calibration ⇾ answer a question or solve a problem before looking at the answer and identify knowledge gaps

“Mastery, especially of complex ideas, skills and processes, is a quest. Don’t assume you’re doing something wrong if learning feels hard.”

Conclusion

Most online courses don’t help you reach your desired outcome. You can spend thousands of dollars and hours without learning anything at all.

Learning doesn’t help you per se — it’s taking the right courses that can make all the difference:

- Check whether the course curriculum goes beyond why and what and teaches the how to do stuff.

- Evaluate whether you’ve got regular touchpoints with your instructor and learning opportunities with fellow students.

- Understand whether you’ll practice your desired skill.

- Look out for evidence-based learning elements such as spacing, retrieval, or reflection.

I’m building a course on how to write online based on evidence-based practices to make the most of your time. You won’t sit in front of pre-recorded videos and struggle to stick with them. If you’re interested in joining a group of 25 people, you can pre-register here.