Computerized flashcard programs make memory a choice.

How often have you read something thinking, “I should remember this,” only to forget it a couple of hours later?

Don’t blame your memory. Forgetting is part of how our brains work.

And contrary to common belief, our brains work not too different from each other (hint: learning styles don’t exist).

Recent advances in cognitive psychology, educational psychology, and neuroscience reveal how humans learn.

Here’s what our brains have in common and how you can make the most of it.

How to prime your memory to remember anything

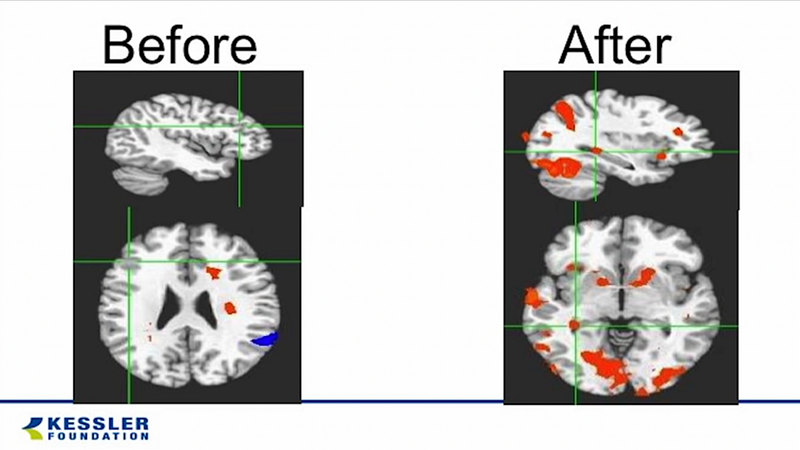

Memory works in three stages: encoding, consolidation/retention, and retrieval. And you need to utilize all three stages to remember anything your want forever.

If you encode something, for example, through watching an online course but don’t practice retention and retrieval, you won’t be able to recall it when needed.

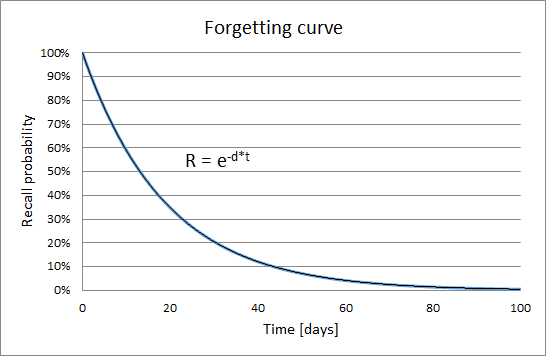

If you hear or read something just once, let’s say by reading a book or watching an online course, you’ll very likely forget it a couple of days later.

That’s the reason why most people can’t recall something from a book they read a while ago when they’d need it.

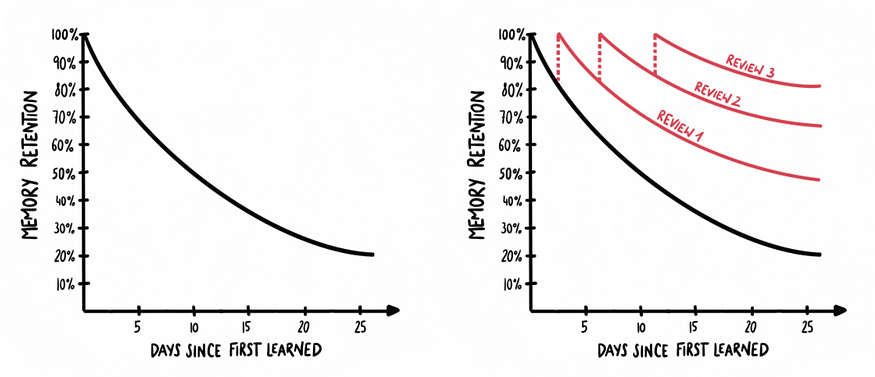

But you can hack your memory by interrupting your forgetting curve.

Encoding knowledge into your memory works best when you reproduce the same piece of information from your mind over increasing time intervals.

And it’s easy. Brilliant minds have come up with software and workflows that help you interrupt your forgetting exactly when you should.

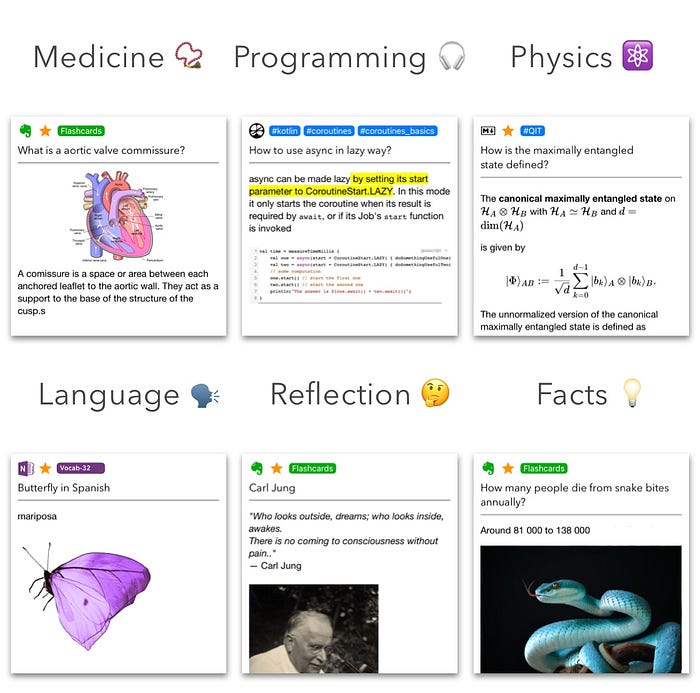

Computerized flashcard programs, such as Anki or Neuracache, help you learn anything by heart forever. In my TEDx talk on mastering learning, I talk about the power of these programs.

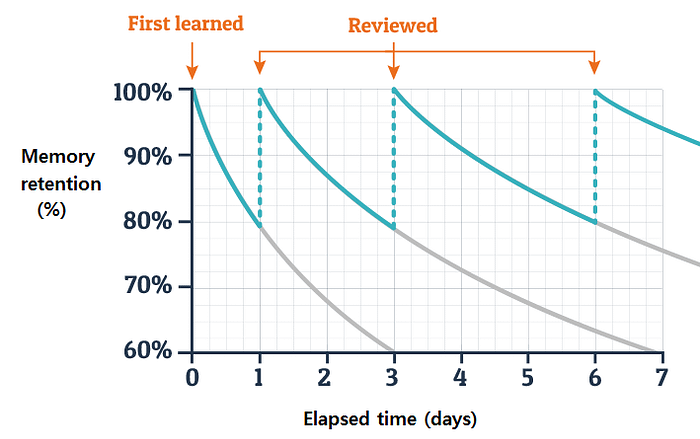

You apply the effective learning strategy of self-testing and the software manages your forgetting curve for maximum retention.

“One-shot learning is not enough. Routinization frees up our prefrontal and parietal circuits, allowing them to attend to other activities. The most effective strategy is to space out learning: a little bit every day.”

— Stanislas Dehaene

If you can answer a question correctly, the time interval between reviews gradually expands. So a one-day gap between reviews becomes two days, then six days, and so on. The idea is that the information is becoming more firmly embedded in your memory, and so requires less frequent review.

Soon you’ll only need to test yourself on information for a few seconds once every one and a half years. Scientist Michael Nielsen has used this system to memorize 20,000 cards and estimates he only needs about 5 minutes of total review time for one piece of information over the entire 20 years.

In essence: spaced repetition memory systems make memory a choice.

But why would you want to remember something forever? There are use-cases that go way beyond exams.

Use cases for hacking your memory

You can learn and all countries of the world and impress your former geography teacher.

But you could also choose some of the following cases and make flashcards really useful for you.

Here’s what I currently use my memory system for:

- Relationships, remembering birthdays, preferences, or experiences. When is Torben’s birthday? What’s Anna’s favourite meal?

- Hobbies, memorizing anything that’s useful for you. What are the first three steps for beatmatching? What direction do my elbows point when doing barbell squats? What should I pay attention to in the cobra yoga pose?

- Job-related information, for example from relevant papers, conferences, or conversations. What were my three biggest learnings from the Education Futures conference in Salzburg? What are the three actions for shifting power in education transformation?

- Habit Stacking, anything you want to do after another habit. When do I practice Anki cards? Which mac command do I use when searching my browser history?

- Random stuff such as favourite places or memory from a holiday, pokemon names, or reflections from your yearly review.

While there are many pre-written decks, you can now see why writing cards yourself is even more meaningful.

“Cards are fundamental building blocks of the mnemonic medium, and card-writing is better thought of as an open-ended skill. Do it poorly, and the mnemonic medium works poorly. Do it superbly well, and the mnemonic medium can work very well indeed. By developing the card-writing skill it’s possible to expand the possibilities of the medium.”

— Andy Matuschack and Michael Nielsen

Four rules for writing great flashcards

Creating the cards by yourself is an important part of understanding and committing.

Here are five rules you want to keep in mind when creating flashcards.

1) Decide whether it’s relevant

It’s tempting to memorize everything you read in books, but you really want to keep it relevant.

Create flashcards for anything that’s worth about five minutes of your lifetime. Because that’s the expected lifetime review time. Michael Nielsen has applied this system for four years and he says it takes < 5 minutes to learn something… forever.

The goal of remembering everything you want is not a self-serving purpose. You ultimately want to apply your knowledge in your day-to-day life; for your job, relationships, or decision-making.

If you try to learn something you don’t care about, you’ll soon stop learning altogether. So choose the stuff you really care about.

“Memorisation is really important, but you have to memorise the right things”

— Daisy Christodoulou

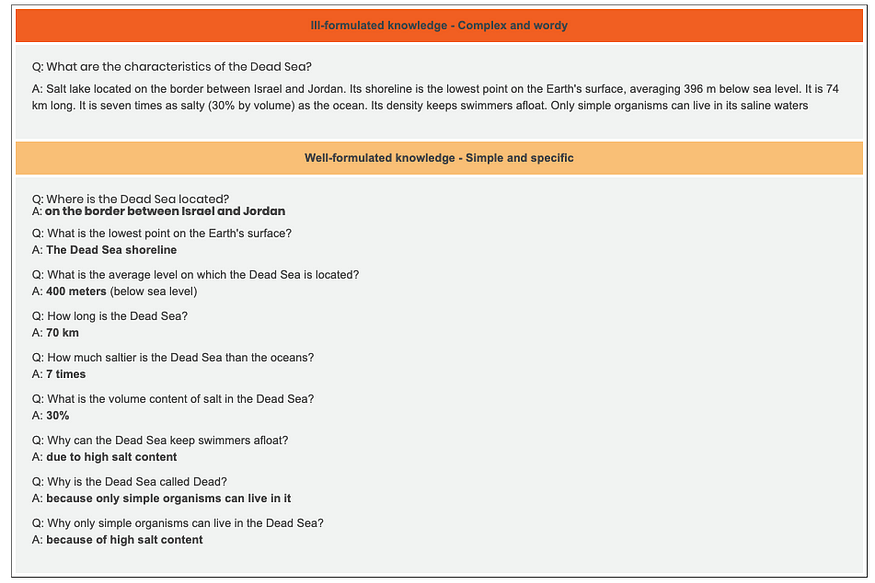

2) Keep the cards really simple.

One of the biggest mistakes new flashcards writers make is creating too dense flashcards.

Simpler is better — stick to the minimum information required, instead of overloading a card.

Here’s an example:

The simpler the easier it’s to remember it and the more flexible you are in its application. However, keep in mind to always add the basics before you dive into the specifics.

Name the main theories of learning (behaviorism, cognitive, constructivism, humanism, and connectivism) before you go into the details of them.

3) Add personal context

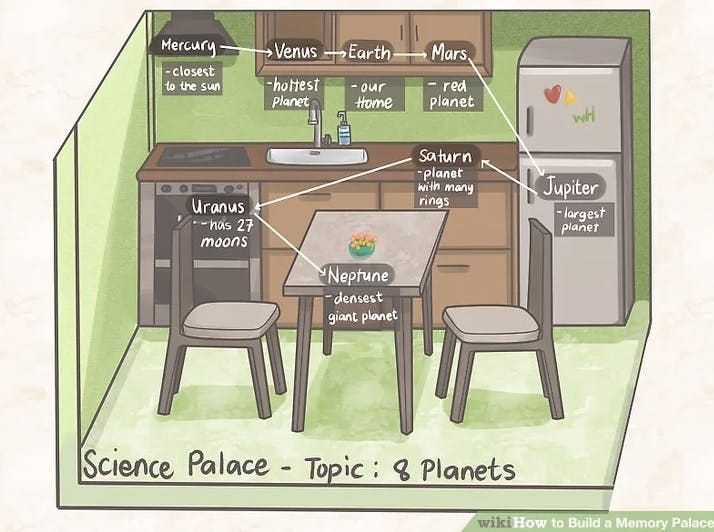

Remember the first memory stage? Encoding works best when you add personal context and meaning to it.

Use your own words to describe a concept rather than copy and come up with personal examples to make learning easier for you.

4) Include real-world retrieval cues

Remember the second and third memory stage? Sorry to do this, but you know you remember best when you recall something from your memory.

So consolidation/retention and retrieval are as crucial as encoding.

There’s a difference between the availability and accessibility of knowledge.

Even if a piece of information is encoded and consolidated, you might have trouble retrieving it (known as the tip of the tongue phenomena).

To memorize flashcards in a way that you can apply them in your life, you want to add retrieval cues.

You can do that by asking questions that are similar to your real-world situations.

For example, instead of asking, what’s the mac shortcut for retrieving your chrome search history, I asked “When researching an article I haven’t saved yet on my Mac, which chrome shortcut do I use to browse through my search history?”

In Conclusion

Spaced repetition memory systems, such as creating flashcards with Anki, make memory a choice. You can remember anything you want, forever.

The goal of fact-learning is not to learn just one random fact — it is to learn thousands, which taken together, form a schema that helps you solve problems, think critically, and make sense of the world.

“Anki isn’t just a tool for memorizing simple facts. It’s a tool for understanding almost anything.”

— Michael Nielson

Want to feel inspired and become smarter about how you learn?

Subscribe free to my Learn Letter. Each Wednesday, you’ll get proven tools and resources that elevate your love for learning.