Science-based strategies your students will thank you for.

I worked hard when I was a teacher for 100 students in a secondary school. But I didn’t use evidence-based methods. I did what everybody else was doing, unknowingly replicating methods that don’t work.

And many popular methods don’t work.

There’s no evidence for the learning styles theory — the belief students learn better through their preference for auditory or visual material.

Eliminating fact-based learning or direct teacher instruction is one of the worst things to do. Factual learning is a precondition for acquiring twenty-first-century skills such as problem-solving, creative and critical thinking.

“When one looks at the scientific evidence about how the brain learns and at the design of our education system, one is forced to conclude that the system actively retards education.”

— Daisy Christodoulou

Evidence-based teaching strategies aren’t part of most teacher training. On the contrary, many educators rely on ineffective teaching techniques.

This is the article I wish I had read during my time as a teacher. There are two key resources I used for writing it:

- Visible Learning, a synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses relating to achievement in school-aged students. The author is John Hattie, a distinguished education researcher, and this work is the result of 15 years of research.

- Seven Myths About Education, a thoroughly researched book by Daisy Christodoulou, a former teacher and Head of Education Research, Ark Teacher Training.

What follows are science-based principles for teaching and increasing student achievement.

1) Give This Kind of Feedback

Since the beginning of behavioural science, we have known that feedback is vital for academic achievement. And yet, the variability of feedback effectiveness is massive.

“The key question is, does feedback help someone understand what they don’t know, what they do know, and where they go? That’s when and why feedback is so powerful, but a lot of feedback doesn’t — and doesn’t have any effect,” John Hattie said in a recent interview with EdWeek. “

So what exactly makes feedback effective?

- Ditch lengthy, hurtful, or personal feedback. Instead, be clear about what you want your students to achieve, know and do.

- Focus on the future. Students want to know how to improve so they can perform better the next time.

- Provide concrete steps. Help students understand where to go next.

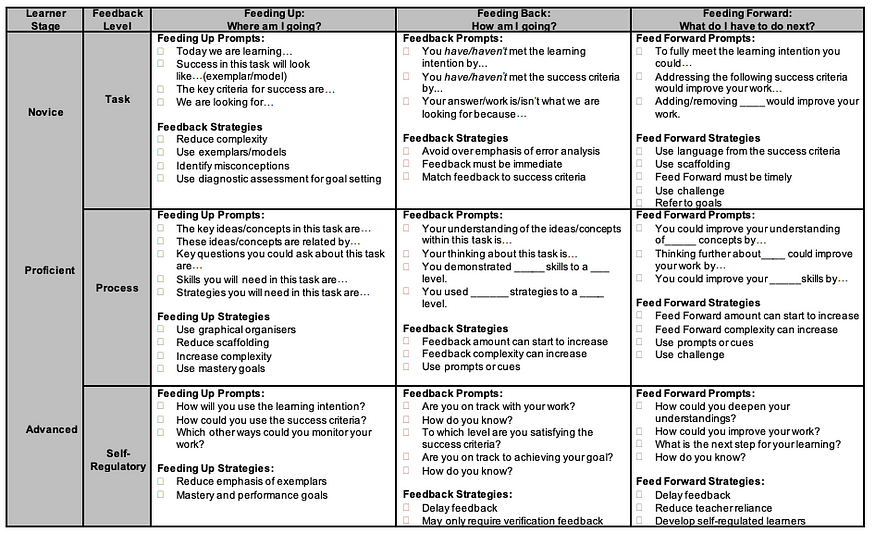

The following chart is a helpful template you can use. It is differentiated between three learner stages (novice, proficient, and advanced) and provides you with phrasing examples.

2) Teach High-Impact Learning Strategies

Different meta-analytic studies (such as this one or this one) evaluate effective strategies for learning.

Researches find that learning strategies help your students achieve higher academic results. Specifically, the following three learning strategies have a high impact on student learning (high impact equals the average effect sizes across different meta-studies).

Elaboration — integrating with prior knowledge

Research shows students learn better when they connect new knowledge to what they already know. Help students link what they’re learning to prior knowledge.

For example, ask your students a couple of questions before they begin to engage with a new topic.

- Does it confirm what you already knew?

- Did it challenge or change what you thought you knew?

- Is it similar to related things?

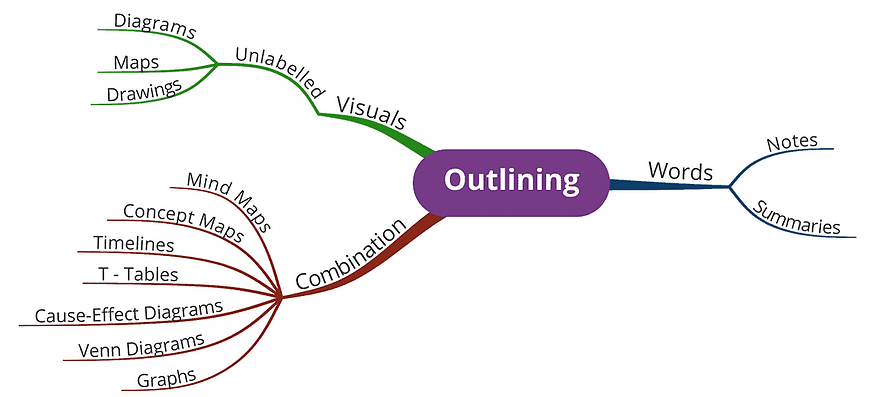

Outlining — identify key points in an organized way

Outlining supports students in organizing, clarifying, and structuring information and ideas. There are different strategies for visual, written, or combined outlines.

While many strategies have their own research behind them (e.g. mind maps), research shows the overarching strategy is impactful for student achievement.

Retrieval — cement new learning into long-term memory

Learning and memory need two components: the learned information itself and a so-called retrieval cue that helps you find the learned material.

Retrieval is a powerful learning strategy because when you recall a memory, both it and its cue are reinforced. With every additional retrieval, you strengthen the connection and can access your memory faster.

Here are two easy-accessible ways to bring retrieval into your classroom:

- Brain Dump. Set a timer to 5–10 minutes and ask students to write down everything they know about a specific subject or concept without using any assistance. Then, ask your students to find out what their neighbour wrote down. Finally, turn it into a whole-class discussion.

- Low-stakes quizzes. Prepare tests that won’t be graded for the start or the end of your lessons. You can also use Kahoot or Poll Everywhere.

3) Harness the Power of Direct Instruction

Remembering my own school days, I demonized direct teacher instruction. It seemed passive and boring.

When I became a teacher, I thought it’d be best if students discover knowledge on their own through a learning environment that’s designed for them.

Paulo Freire, a leading advocate of critical pedagogy, talks in his widely cited book “Pedagogy of the Oppressed” about the co-construction of knowledge. Teachers are students, and students are teachers.

He writes, “Education must begin with the solution of the teacher-student contradiction, by reconciling the poles of the contradiction SO that both are simultaneously teachers and students.”

Freire goes on to explain why teaching facts to students prevents understanding. Other educationalists, such as Russeau, join his reasoning.

If you’ve read about 21st-century skills, you will likely have stumbled upon sentences such as an “education that requires you to memorize facts will prevent them from being able to work, learn and solve problems independently.”

Daisy Christodoulou analyzes that Ofsted, a school inspection service that influences teaching practice in the UK, sees “teacher-led fact-learning as highly problematic.”

But all of the above is wrong. Again Christodoulou:

“They argue, correctly, that the aim of schooling should be for pupils to be able to work, learn and solve problems independently. But they then assume, incorrectly, that the best method for achieving such independence is always to learn independently. This is not the case.”

“Teacher instruction is vitally necessary to become an independent learner.”

— Daisy Christodoulou

John Hattie’s evaluation of over 800 meta-analyses comes to the same conclusion. Teacher instruction is the third most powerful influence on achievement.

“While the final aim of education is for our pupils to be able to work independently, endlessly asking them to work independently is not an effective method for achieving this aim.”

— John Hattie

So how does direct instruction work? John Hattie explains:

“In a nutshell: The teacher decides the learning intentions and success criteria, makes them transparent to the students, demonstrates them by modelling, evaluates if they understand what they have been told by checking for understanding, and re-telling them what they have told by tying it all together with closure.”

One example I do in my writing online course is the “I-Do, We-Do, You-Do” model. I explain why we learn something and how we define success; I then model the desired skill by doing it myself, we then do it together in a plenum before students go off themselves to breakout rooms or working time and apply it for themselves.

In Conclusion

About a hundred years ago, Benjamin Franklin seemed to have said, “Tell me, and I forget. Teach me, and I remember. Involve me, and I learn.”

Hundred years later, most teachers and students are still unclear about the best learning methods.

But thanks to the science of learning, a mix of cognitive and social psychology, neuroscience, and educational sciences, we do know a lot of what works and what doesn’t. The above strategies can help your students achieve more.

Want to feel inspired and become smarter about how you learn?

Subscribe free to my Learn Letter. Each Wednesday, you’ll get proven tools and resources that elevate your love for learning.