This is how networked thought transformed my writing process and cut my research writing time in half

“Are you sure reading all those books is worth your time?” my fiancé asked me last fall. He found a weak spot. I’d been contemplating my reading habits for quite some time.

While I knew how you could remember what you read, I felt my reading was inefficient.

I read a book, along with 50 articles a week, and encounter many interesting ideas. While I had a method to remember what I read, I felt my reading and creative workflow was inefficient.

But when it comes to writing, it often happened that I knew I read something about the topic somewhere. Despite my summaries, I struggled to recall where the information was, making it difficult to reference. I’d spend half an hour browsing through side notes in a book’s margins, digital notes, and bullet journals without a result. I’d continue without the information, frustrated.

So when my partner asked the question, my answer was unconvinced, “Reading is great. I just haven’t found the right system to work with it yet.”

That’s why something clicked when I first heard the term “Zettelkasten” in one of Ali Abdaal’s videos. Yet, I struggled to summarize the Zettelkasten — even Ali admitted that he hadn’t grasped it fully.

Whenever I’m hooked, I enter a tunnel. I watched and read every tutorial I could find on the internet, read the original German texts, studied Sönke Ahren’s how-to guide, researched coaches, and hired one. Since March, I also help my coaching clients set up their system.

I’m so in love with my Zettelkasten, my fiancé sometimes feels betrayed. These are the ways my digital brain has transformed my thinking, learning, and writing.

- Increased productivity. I write and create faster. I no longer waste time searching for sources. Instead of using my brain to browse through books and digital bookmark notes, I have everything in one place. A research-based 1,300-word article used to take me three hours to write— with Zettelkasten, it takes me one and a half.

- Original ideas. Whenever I write or research a topic, I browse through my Roamkasten and find what I’m looking for, plus connections between domains I hadn’t thought about in the first place.

- Better thinking. New information challenges my thinking and helps me overcome cognitive biases. I gain a deeper understanding of everything I read.

- Maximum retention. I have a place that stores everything valuable from what I watch, read, or listen to. It helped me develop my worldview by comparing evidence, ideas, and arguments.

What follows is a crisp description of how the Zettelkasten works and the exact system I follow to set it up in Roam. Everything you’ll need to set this up is in this article.

Table of Contents

1 Zettelkasten - What Is It and How Does It Work?

1.1 Luhmann’s Zettelkasten as fuel for his productivity

1.2 Zettelkasten's three types of notes

1.3 Zettelkasten's 4 core principles

2 Roam Research- What Is It and How Does It Work?

2.1 Roam's Value Proposition

2.2 RoamResearch functions you need for building a Zettelkasten

3 Roamkasten - How to Set up Your Zettelkasten in Roam

3.1 How to capture fleeting notes

3.2 How to take great literature notes

3.3 How to create permanent notes

3.4 Tying it all together in the index of the permanent note

4 How I Use the Roamkasten in My Writing Process

4.1 How I seek great content

4.2 How I block out consumption time

4.3 My automated capturing process

4.4 How I use new ideas for networked thought

4.5 How I write to learn

1. Zettelkasten — What Is It and How Does It Work?

What follows is a brief description of its origins, the four types of note hierarchies, and the key principles.

1.1 Luhmann’s Zettelkasten as fuel for his productivity

Niklas Luhmann was a social scientist and philosopher, and researchers consider Luhmann one of the most important social theorists of the 20th century.

During his life, he wrote 73 books and almost 400 research articles on various topics, including politics, art, ecology, media, law, and the economy.

When someone asked him how he published so much, Luhmann replied, “I’m not thinking everything on my own. Much of it happens in my Zettelkasten. My productivity is largely explained by the Zettelkasten method.”

“Zettel” is the German word for paper slip, “Kasten” means cabinet or box. During his lifetime, he wrote and kept 90,000 index cards in his slip box. All notes were digitized by the University of Bielefeld in 2019, and the original German version is available online. But this is what it originally looked like:

1.2 Zettelkasten’s three types of notes

At its core, the Zettelkasten has different levels of note-taking. I wrote an entire article about the notes hierarchy. Here’s the quintessence of the three different note types:

Fleeting Notes: Fleeting notes are ideas that pop into your mind as you go through your day. They can be really short, just like one word. You don’t need to organize them.

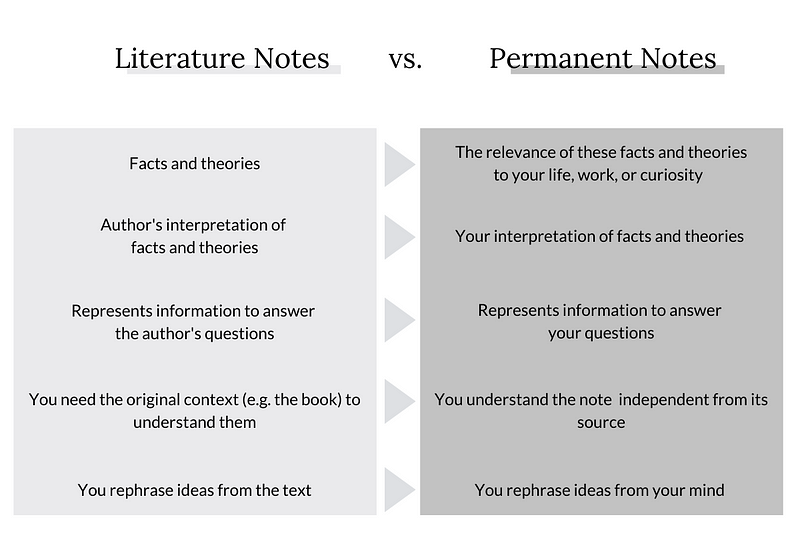

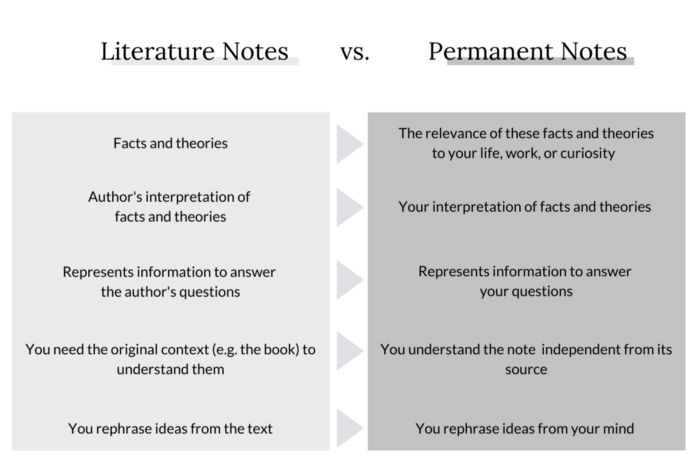

Literature Notes: You capture literature notes from the content you consume. It’s your bullet-point summary from other people’s ideas. I create these notes for all books, podcasts, articles, or videos I find valuable.

Permanent Notes: When you create permanent notes, you think for yourself. In contrast to literature notes, you don’t summarize somebody else’s thoughts. You don’t just copy ideas but develop, remix, and contradict them. You create arguments and discussions. By writing your idea down, you put pressure on your thinking and transform vague thoughts into clear points.

1.3 Zettelkasten’s 4 core principles

You want to keep in mind a few core principles to make the most of your Zettelkasten.

1) Context and Connection. A note is only as useful as its context. A note’s true value unfolds in its network of connections and relationships to others. You don’t tag notes in the context you found them. Instead, tag them in the context in which you want to discover them. By connecting new notes with existing notes, you broaden your thinking.

2) The usefulness grows with time. When you store more, the connections and interlinks grow stronger. The Zettelkasten becomes more useful as it grows because you can discover related ideas you hadn’t thought of in the first place. As Sönke Ahrens writes: “The more content it contains, the more connections it can provide, and the easier it becomes to add new entries in a smart way and receive useful suggestions.”

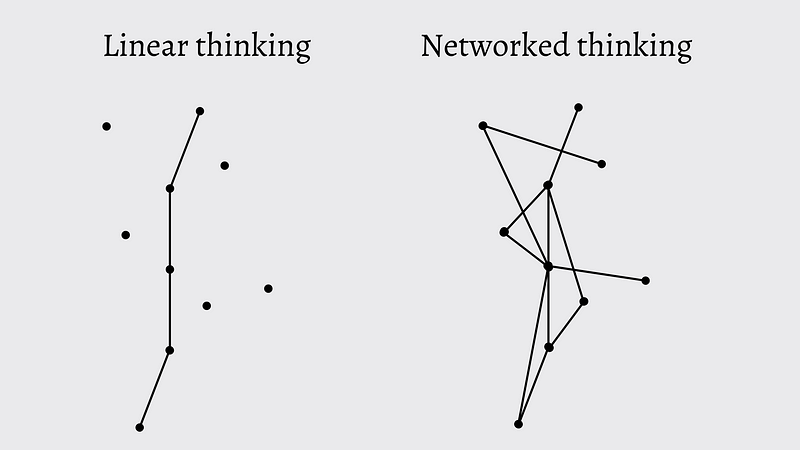

3) Networked instead of hierarchical note-taking. The problem with traditional note-taking approaches (even with apps such as Notion or Evernote) is the linear structure. Ideas get locked in a folder and, with time, are forgotten. With the Zettelkasten, it’s different.

As Luhmann writes: “Given this technique, it is less important where we place a new note. If there are several possibilities, we can solve the problem as we wish and just record the connection by a link or reference.”

Can you see it’s the same number of thoughts but more connections?

Networked thinking includes interactions and relationships between thoughts. Connecting notes leads to new ideas and better ways of thinking. As you will see in some minutes, the Roamkasten has an inbuilt feature (tagging and bi-directional linking) that will help you make more connections between individual thoughts. Thereby, you create a larger web of ideas.

Science supports the value proposition of networked note-taking. As researchers state: “Studies suggest that nearly all non-linear note-taking strategies (e.g. with an outline or a matrix framework) benefit learning outcomes more than the linear recording of information, with graphs and concept maps especially fostering the selection and organization of information. As a consequence, the remembering of information is most effective with non-linear strategies.”

4) Idea Serendipity. Because of the interconnection, the increased value with growth, and the networked note-taking, you tumble upon ideas you have never thought of. Day by day, the slip box will transform into an idea generation machine. You’ll be more creative as you find past ideas and new connections.

Luhmann writes: “The slip box provides combinatorial possibilities which were never planned, never preconceived, or conceived in this way.”

2. Roam Research — What Is It and How Does It Work?

2.1 Roam’s Value Proposition

Roam is an online workspace for organizing and evaluating your knowledge. Unlike linear cabinet tools, Roam allows you to remix and connect ideas, where each note represents a node in a dynamic network.

This leads to vast application opportunities. As Anne-Laure Le Cunff writes: “Roam Research is a tool powerful enough to manage an end-to-end writing workflow, from research and note-taking (input) to writing an original article (output).”

To give you a sneak peek of what you can expect, here’s an example of how I wrote this paragraph using Roam.

Disclaimer: I'm not sponsored by Roam or Readwise. I pay for both tools 23$ a month (15$ for Roam and 8$ for Readwise). You can also work with TiddlyWiki (free and open-source), Obsidian, RemNote, Amplenote, and Org-roam. And alternative to Readwise is importing highlights manually.

2.2 The only five RoamResearch functions you need for building a Zettelkasten

Think of Roam like Excel. It has a low floor but a high ceiling. You can use Excel for simple things like a grocery list and create a table. Yet, some functions allow entire businesses to run off Excel sheets.

“Roam is simple but not easy,” founder Conor White Sullivan said in an interview. Unlike Notion, Roam didn’t dumb down to the lowest common denominator. Roam’s strategy is to attract people who are willing to learn using a power tool.

Once you know your way around Roam, you’ve unlocked a programming language for personal productivity and development. Here are the five key things you need to know about Roam to set up your Zettelkasten.

#1 The Daily Notes

Every time you open Roam, you will find yourself on the Daily Notes page. Think of it as your entry door whenever you want to start working with your Zettelkasten.

If you’re used to hierarchical note-taking apps such as Notion, or Evernote, missing folders might feel weird first. But you’ll soon understand how this structure accelerates your learning.

You don’t need folders to store a specific note because you link them with each other. In Luhmann’s words: “We can choose the route of thematic specialization (such as notes about governmental liability), or we can choose the route of an open organization.”

Why it’s relevant: Whenever you capture something, just type it as a bullet in your daily notes page and use tags or pages to connect it with existing notes.

#2 Formatting text

These are the three ways I use Roam to format text: ^^highlighting^^, **bolding**, and making text _italic_. Here’s how it works with shortcuts:

Why it’s relevant: You’ll use these functions when you go through your literature notes or want to highlight specific parts of your text.

#3 Creating pages (and bi-directional links)

See how you can create new pages with brackets [[]] and hashtags #. Both ways have the same function; they just look different. You can use either one. All pages are tags, and all tags are pages.

Note: Pages are case-sensitive. For example, [[Brain]] and [[brain]] will exist as two separate pages, the one called “Brain” and the other “brain.”

This function is networked thought in action and the reason you don’t need folders. When you create a page Roam automatically adds all related blocks from your database as references to your page.

For example, I have a page called [[quote]] where I collect my favorite quotes. This morning, I saw a quote I liked and typed it into my daily notes. I added #quote behind it. When I now click on #quote (or [[quote]]), it shows up with all the other quotes I labeled with this tag.

![The author shows their page called [[quote]] where they collect their favorite quotes.](https://cdn-images-1.medium.com/max/800/1*ibWuKcMv3vLE7zS4-Ja81g.gif)

Plus, what makes pages even more powerful is that Roam suggests links you haven’t referenced. When I click on the “Unlinked References” on my [[quote]] page, I see potentially related bullets and can add them to my page by clicking “Link.”

Why it’s relevant: You will need pages to create your literature and permanent notes. Moreover, you’ll use them to find relevant references whenever you write or research something. Pages are the engine for bi-directional linking.

#4 Opening a sidebar

See how the sidebar opens by shift-clicking on a page. You can open as many pages on the sidebar as you like.

Why it’s relevant: This is extremely useful when you research or write. When you’re working on one article, you can open the sidebar and find all the relevant pages. You can simply pull notes from them.

#5 Using Templates

To create a template, you can use the following structure:

• TemplateName #roam/templates

• [[Template Title]]

• Your template's contentWhen you want to use your templates, you simply type ;; and the template name will show up. Here’s what it looks like in my workflow when creating a permanent note.

Why it’s relevant: You’ll use templates for your literature and your permanent notes. Templates save you time and make your structure consistent. I’ll share my templates with you in a bit.

Extra tweaks

There are way more things you can do with Roam, but these five functions are all you need for building your Zettelkasten in Roam.

Suppose you’re curious what else you can do type/inside your database. You’ll discover some more useful functions, such as TODOs and a Pomodoro Timer.

When you click on the question mark in the top right corner, you’ll discover more shortcuts. For future inspiration, you might want to bookmark RoamBrain’s resources. But as a start, I suggest you go with the above and ignore the rest.

3. Roamkasten — How to Set up Your Zettelkasten in Roam

Now you know how Zettelkasten works (see 1) and the key Roam functions to build your own (see 2). This part will outline how you can build your slip box in Roam.

3.1 How to capture fleeting notes

Fleeting notes collect the ideas from your mind as you go through your day. My fleeting notes are sometimes really short, like a single word. Fleeting notes serve as idea reminders. They don’t require a fancy workflow. You just need a way to capture them.

I use a simple notebook or add notes on the books I read, in my bullet journal, or my Kindle notes. A preinstalled notes app works as well. Alternatively, you can also use Roam on your smartphone.

Don’t stress about fleeting notes — they are simply your stepping stones for turning literature notes into permanent notes.

3.2 How to take great literature notes

Create these notes whenever you find something valuable in the content you consume. You can take literature notes from books, podcasts, articles, online courses, videos, or even conversations.

There are three rules for taking literature notes: make them brief, use your own words, and note bibliographic references.

Whenever I create literature notes, I follow the template’s structure. Feel free to copy and edit it in your own database.

To do so, I suggest you create a page called [[templates]]. You’ll have all templates in one place. Once you have the [[templates]] page, simply copy the following lines into it.

•LN 📙 Template #roam/templatesLN 📙 <BookTitle>]]

• [[Author:: <Firstname Lastname>

•Tags:: # (In which circumstance do I want to find this

•

note? What would I google for to find this note (not a

general single term), When and how will I use this

idea?)Type:: #book #article #podcast #video #onlinecourse

•Status:: #ToCreate #ToProcess #Reviewed

•Recommended by:: <Firstname Lastname>

••Source::• **What's interesting about this?**•What’s so relevant it’s worth noting down?**

• **•

The “Tags” are crucial for your Zettelkasten’s quality. As stated in the core principles, a note is only as valuable as its context. I borrowed the questions in “Tags” from Sönke Ahren’s How to Take Smart Notes. They will help you create good cross-references.

Assign tags by thinking about topics you’re working on, not by looking at the note in isolation. By using helpful tags, you unlock the bi-directional linking power. Once you search for answers with a question in mind, the Roamkasten will give you all the answers and related ideas.

3.3 How to create permanent notes

You create permanent notes drawing inspiration from your literature and fleeting notes. Ideally, you create them once a day (I never meet that goal and feel super proud with 4–5 permanent notes a week).

When you write down a permanent note, make sure it contains only a single idea. If you have a train of thought, create multiple permanent notes. By using the principle of atomicity, you can better link your ideas.

When you create permanent notes, you don’t write a full paper. You write ideas. That’s how your permanent notes become reusable.

While your literature notes are bullets and fragments, your permanent notes should sound like written prose. A reader of your permanent note should understand it without reading the source that led to your idea.

If you’re a writer, the number of permanent notes you write in a day might be the single best metric to track your progress.

Again, here’s my template for your reference. I remove the #ToFile once I filed the permanent note with a number to my existing index, as I’ll show in 3.4.

•PN 📗 Template #roam/templates[[PN 📗 X.x.X.X <Insert Note> ]]

•References:: <Source> by <Firstname Lastname>

•Keywords::[[permanent notes]] + #Tags (In which

•

circumstance do I want to find this note? What would I

google for to find this note (not a general single

term), When and how will I use this idea?)Relevant other PNs:: (link PNs that relate to this

•

note: How does this idea fit your existing knowledge?

Does it correct, challenge, support, upgrade, or

contradict what you already noted?)•#ToFile

In the beginning, I struggled to write permanent notes. I thought of them as a holy grail. But they aren’t — permanent notes are a work in progress.

Don’t be afraid to write them. You can change and update them whenever you want: what permanent really means is that they’re permanently useful to you.

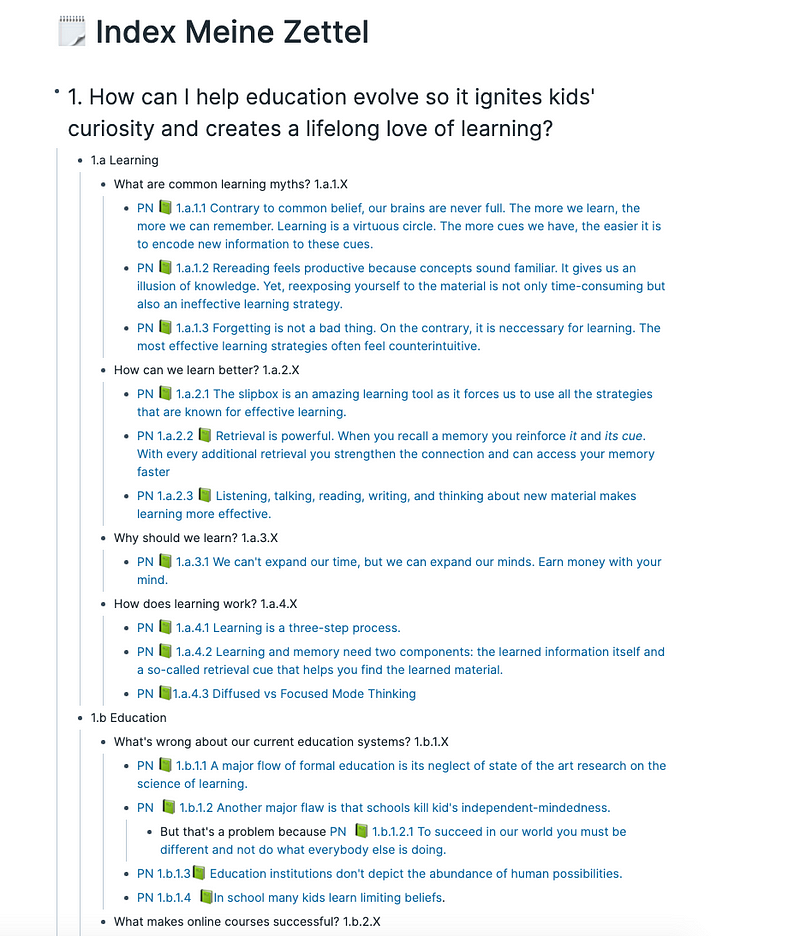

3.4 Tying it all together in the index of the permanent note

As there are no folders, you need an index or register to keep an overview. In Luhmann’s words: “Considering the absence of a systematic order, we must regulate the process of rediscovery of notes, for we cannot rely on our memory of numbers.”

You can label your permanent notes as you like and build indefinite internal branches. As Luhmann writes: “We do not need to add notes at the end, but we can connect them anywhere — even to a particular word in the middle of a continuous text. A slip with number 57/12 can then be continued with 57/13, etc. At the same time, it can be supplemented at a certain word or thought by 57/12a or 57/12b, etc. Internally, this slip can be complemented by 57/12a1, etc.”

Here’s an example of the branching I use for my permanent notes in my notes index:

“Every intellectual endeavour starts with a note.”

4. How I Use the Roamkasten in My Writing Process

There are five steps to my creative workflow: seek, consume, capture, network, and write.

4.1 How I seek great content

My creative process starts with the search for great content. To do so, I rely on my friends’ recommendations and my curiosity. I also use content discovery tools like Feedly, Bookshlf, GoodReads, Refind, Inoreader, Flipboard, or Mailbrew. When you feed your brain with good content, it will develop good ideas.

4.2 How I block out consumption time

I block undistracted consumption time, mostly an hour of no phone book reading time before lunch and bed. That’s how I read around 50–60 books a year.

Yet, I don’t focus on quantity and keep Naval Ravikant’s advice in mind: “Reading a book isn’t a race — the better the book, the more slowly it should be absorbed.” Slow reading for deep learning helps you read better.

4.3 My automated capturing process

While reading, watching videos, or listening to podcasts, I always take a few notes (unless I’m reading fiction for fun). My inner metacognition dialogue sounds like “This concept relates to…,” “This argument conflicts with…,” “I don’t know how… .”

I take my notes within the source. I use my Kindle for book notes, Readwise for analog notes and web highlights, Textsniper for capturing text from images and slides, Reclipped for videos, and Airr for podcast notes.

I’m generous with my notes. According to evidence, the more notes you take, the more information you can remember. From my Readwise account, all highlights and notes are imported to my Roam database.

4.4 How I use new ideas for networked thought

The imported highlights and notes within Roam serve as a starting point for creating literature and permanent notes. Whenever I finish a book, I sit down with my laptop and use the roam template for literature notes (see 3.2).

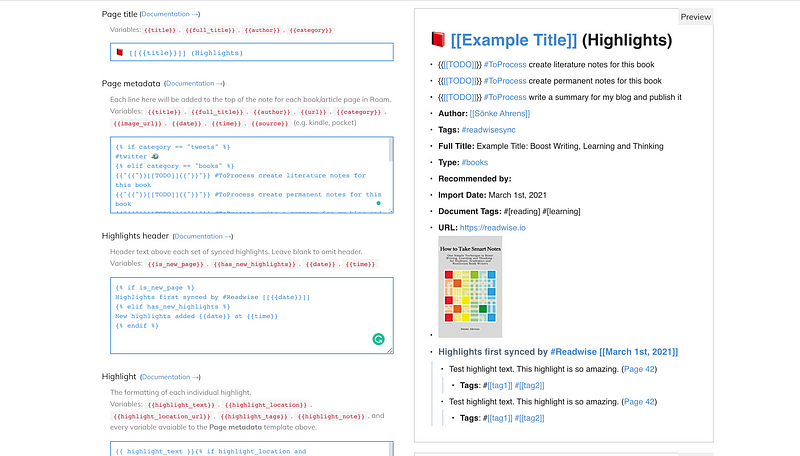

To make sure I don’t forget to work with my highlights, I customized my Readwise to Roam integration like this.

Here’s the code I used for the Page metadata. Feel free to copy it (and let me know if you have some ideas for improvement):

{% if category == "tweets" %}

#twitter 🐦

{% elif category == "books" %}

{{"{{"}}[[TODO]]{{"}}"}} #ToProcess create literature notes for this book

{{"{{"}}[[TODO]]{{"}}"}} #ToProcess create permanent notes for this book

{{"{{"}}[[TODO]]{{"}}"}} #ToProcess write a summary for my blog and publish it

{% else %}

podcast or article

{% endif %}

Author:: [[{{author}}]]

Tags:: #readwisesync

Full Title:: {{full_title}}

Type:: #{{category}}

Recommended by::

Import Date:: {{date}}

{% if document_tags %}Document Tags:: {% for tag in document_tags %}#[[{{tag}}]] {% endfor %} {% endif %}

{% if url %}URL:: {{url}}{% endif %}

{% if image_url %}{% endif %}

From this import, my Roamkasten process begins. I use the ;; to retrieve the literature note template (see 3.2). While and after creating literature notes, I create permanent notes (see 3.3). Whenever I’m done with this work, I tick off the TODOs from my import template.

4.5 How I write to learn

Writing to me means not only thinking but also learning, creating, evolving. It means getting at the deeper meaning of everything around me. For me, it’s the best way for life-long learning.

My entire writing process happens within Roam. I start by brainstorming ten headline ideas and let my mastermind groups pick their favorite ones.

On my daily notes page in Roam, I create a page for the chosen title and use the article template to get started. Here’s how I start my writing process almost every morning.

I create an outline with subheads and then search for interesting ideas and thoughts to add to my articles by opening the sidebar.

Once I’m done writing (which typically takes two times 50 minutes), I copy the Roam text to this free tool to remove the markup language. Then, I copy the text into a new Medium story and go through two rounds of editing.

“Writing is not what follows research, learning or studying, it is the medium of all this work. […] Those who take smart notes will never have the problem of a blank screen again.”

5. Final Thoughts

You won’t see the benefits within the first weeks. To reap them, your Zettelkasten must mature. But after some months, the power will unlock. Or, as Luhmann writes: “The slip box needs a number of years in order to reach critical mass. Until then, it functions as a mere container from which we can retrieve what we put in.”

In the beginning, you might ask yourself whether you’re doing it right. Even if you mix up some structures, it doesn’t really matter. The researchers who digitized Luhmann’s Zettelkasten found inconsistencies in his labeling and interlinking — his Zettelkasten was far from perfect and still made him one of the biggest scientific contributors of his time.

You’ll never again encounter a blank page and have no idea what to write about. Instead, you receive useful suggestions of previous ideas that you’ll have too much to write about.

If you follow the above steps, you can learn better, think better, publish more, and be more creative. My Roamkasten transformed my creative process. I hope it will do the same for you.