An actionable guide for purpose-driven businesses

In December 2019, we couldn’t have known that founding a remote NGO would turn out to be the only way to bring an idea to life in 2020.

What started with a social media post from one of our co-founders turned into a fast-growing nonprofit organization with a 20 people team and a 28% user growth rate.

As we’re a digital match-making platform for equal educational opportunity, the pandemic didn’t harm us. On the contrary, we have a strong, growing demand from students with non-academic families and an even faster-growing supply of supporting mentors.

Our world needs more purpose-driven businesses tackling education, climate change, or other social challenges. And as this story will reveal, starting from home can be a great opportunity to found an NGO.

I’m one of the co-founders, and I’ve been working on the core-team since day one. Together with the other founders, we analyzed our story and came up with an actionable guide on how to remotely start and scale a purpose-driven idea.

1. Sharing the ‘Why’ and ‘What’ on LinkedIn

To start an NGO, other people first need to know about the idea. Simon Sinek’s classic golden circle is a great way to structure the initial social media post.

In this manner, our co-founder Kevin articulated his idea on LinkedIn. A post that eventually would reach more than 234.000 people.

“Being the first in my family to go to uni, I faced multiple headwinds as higher education was not considered to be something one should aim for and could afford. What started as an experiment ended up in six years full of studying and working in Cologne, Shanghai, Frankfurt, Bangkok, Munich, Lisbon, and Milan.”

After empathetically sharing the why — his personal, educational path — he stated what he plans to do to tackle the problem:

“In 2020, I want to further work on a platform that aims at building a community to connect those who want to study as the first in their family with those who already did it. Your family background should not predetermine your educational path!”

I asked Kevin how much time it took him to craft this post and whether he expected virality. “I thought back and forth how exactly I’d write what I mean,” he said, “but I didn’t expect to recruit an entire team for my idea.”

So while one can never plan the effects of a social media post, this example demonstrates the importance of clear communication. By putting some hours into crafting a meaningful, personal post with a clear why and an achievable what, it’s likely one finds people who want to join forces.

The quality of a post often increases in direct proportion to how much time we spend crafting it. That’s why it makes sense to put work into the initial message.

2. Gathering A Group of Like-minded People

A shareable and likable post is a great lever to recruit people who want to work on a solution. After his post, Kevin received countless comments and messages from people who wanted to support or team-up.

To capture the momentum, he created a closed LinkedIn group and added all people who expressed interest. In retrospect, this move was genius. The group formation turned passive bystanders into direct idea stakeholders.

Once in the group, I felt I was part of meaningful creation. And many others must have felt the same way. When Kevin suggested doodling a kick-off call, 30 people joined.

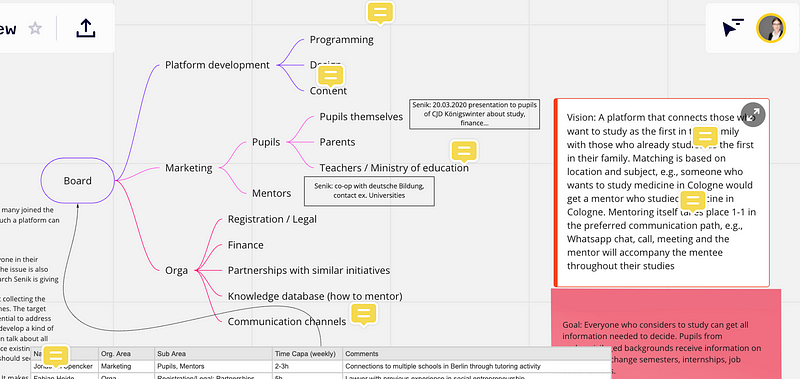

To structure the conversation, we used a collaboration tool like Miro. As the picture shows, we wrote down the vision, the required task forces, and a rough timeline.

With a protocol follow-up in the LinkedIn group and the opportunity to contribute to the Miro board, all idea stakeholders started with equal alignment. Plus, the transparent co-creation set the tone for the next steps.

3. Building a Self-Selected Core Team

After forming a common understanding within the LinkedIn group, it soon became clear we couldn’t effectively work on a 150 people team. Kevin could have started a formal selection process. But he didn’t. Instead, the core team formed through self-selection.

In Germany, one needs 7 founders to register an NGO officially. But instead of starting a competition, the communication was clear: Those who have time, and the drive, will become part of the core team. Those who don’t will remain supports and receive regular updates within the LinkedIn group.

When I asked Kevin about the selection process, he said: “I think there were 3–4 people who didn’t end up in the core team. Not because we pushed them out, but rather because they didn’t want to or didn’t have the drive themselves.” Reflecting on the formation, he concluded: “Self-selection is really the crucial point.”

Self-selection made our team diverse. Since the core team formation, it’s been a key asset to have a lawyer, a techie, an HR expert, a visual wizard, a sales guru, students, business developers, and process and strategy consultants in our team. What unites us is the joint mission to tackle education equality by creating a scalable product for students with non-academic backgrounds.

Within the first 11 months since our launch, we bootstrapped the business. We didn’t need to pay for external services. Remote founding has the benefits of large network effects. As we bring 12 different circles of friends, there’s always somebody who knows a person with the skills required to solve our next problem.

4. Setting a Launch Date for the MVP

Once the founding team was set, and we settled on communication tools and regular touchpoints. We had a bi-weekly Saturday morning call to discuss our progress. Yet, three months in, we got off-track.

“We were in a phase where things got vague,” my co-founder describes. “We always tried to develop further, to improve processes, but at the same time, many people lost their motivation because we had been working for long without visible results.”

To regain our drive, Kevin set a launch date for our minimum viable product. With a clear going-life date in mind, our team got back on track. We launched a website, set up a mentoring process, developed marketing strategies, created content, and built a community.

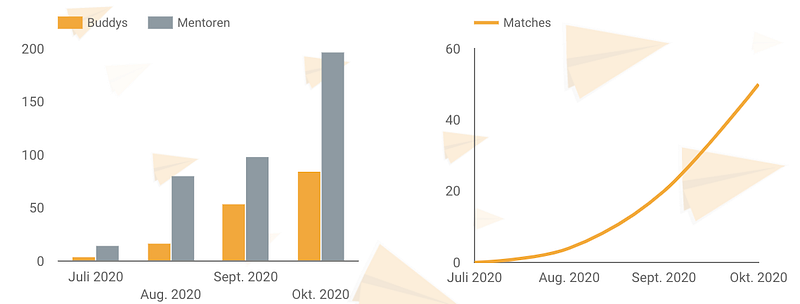

Today, three months after our launch date, we’ve more than 200 mentors, 80 mentees, and crossed the 50 match mark.

Struggles Along The Way

While many things went smoothly, there were three key obstacles along the way. Here are the things only hindsight can reveal.

#1 Implement Slack as a Communication Platform

For most of the early days, we had all of our discussions on WhatsApp. Many ideas were lost. We should have switched to Slack earlier.

#2 Protocols and To-Do Lists

As within many organizations, many of our meetings were unproductive. While the talk time felt nice, we struggled (and still do) to have a team-wide agenda, protocol, and to-do list system.

#3 Expectation Management

As there was no formal recruiting process, and all of us work voluntarily, we never discussed how much time we expect each team member to contribute.

Key Takeaways

Starting from home can be an advantage for building an NGO. It helps you find and team with people you didn’t even know existed.

It forces you to focus on finding a vision worth building instead of fantasizing about vague ideas on societal improvements.

After all, your idea takes off or sinks. To increase your chances of success, remember:

- A well-crafted LinkedIn Post (including why and what).

- The formation of a large pool of like-minded people.

- Building a driven, self-selected core team.

- Setting an MVP launch date to increase team motivation.

Starting and building an NGO from home can work. Yet, it also takes work.

But who’s gonna make it work, if not you?