A guide for applying evidence-based learning strategies to reading any non-fiction book, and retaining what you read.

At age 18, I felt most school lessons were time-wasters. To save future pupil generations from what I had suffered through, I decided to change the education system. And if that wasn’t naïve enough, I assumed studying business education would get me there.

Where, if not in an education program at university, should you learn how to learn?

I was wrong. There were no classes on learning or cognitive science. Being assigned dry, academic, self-promoted professor books, I hadn’t figured how the right books could teach you anything. Instead, I asked the best-performing fellow students about their learning techniques and copied their bulk-learning and memorizing. But after graduation, I felt dumb. I forgot almost everything from my classes.

A Bachelor’s degree taught me how to learn to ace exams. But it didn’t teach me how to learn to remember.

Different studies reveal most students never learn how to learn. Kornell & Bjork and Hartwig & Dunlosky, for example, show that 65% to 80% of students answered “no” to the question “Do you study the way you do because somebody taught you to study that way?”

From the ones who answered “yes,” some likely watched the most-popular Coursera course of all time: Dr. Barabara Oakley’s free course on “Learning how to Learn.” So did I. And while this course taught me about chunking, recalling, and interleaving, I learned something more useful: the existence of non-fiction literature that can teach you anything.

So I read—a lot. Since 2017 I have read about 150 non-fiction books about how our minds work, how children learn, and how education might solve global health problems, to name a few. I was fascinated by education and learning; I skipped the corporate career and became a Teach for All fellow to learn more about learning.

Yet, about 80 books into my reading journey, something felt odd. Whenever a conversation revolved around a serious non-fiction book I read, such as ‘Sapiens’ or ‘Thinking Fast and Slow,’ I could never remember much. Turns out, I hadn’t absorbed as much information as I’d believed. Since I couldn’t remember much, I felt as though reading wasn’t an investment in knowledge but mere entertainment.

I know many others feel the same. When I opened up about my struggles, many others confessed they also can’t remember most of what they read, as if forgetting is a character flaw. But it isn’t.

Forgetting most of what we read isn’t a character flaw. It’s the way we work with books that’s flawed.

Once I understood how we learn — through online courses, books, and Teach for All — I realized there’s a better way to read. Most people rely on techniques like highlighting, rereading, or, worst of all, completely passive reading, which are highly ineffective. It’s only logical most people forget almost anything they read.

Since I started applying evidence-based learning strategies to reading non-fiction books, many things have changed. I can explain complex ideas during dinner conversations. I can recall interesting concepts and link them in my writing or podcasts. As a result, people come to me for all kinds of advice. Plus, I was invited to speak at panel discussions, got paid for content curation, and have received high-level job opportunities. I finally feel like reading is a true investment in knowledge.

And if I, a former naïve clueless mouflon monster can do it, you can do it, too. But before you learn how this system works, let’s explore why it works. To become a truly effective learner, we need to understand the key aspects of human learning and memory.

What’s the Architecture of Human Learning and Memory?

Human brains don’t work like recording devices. We don’t absorb information and knowledge by reading sentences.

Instead, we store new information in terms of its meaning to our existing memory. And we give new information meaning by actively participating in the learning process — we interpret, connect, interrelate, or elaborate. To remember new information, we not only need to know it but also to know how it relates to what we already know.

That’s why memory and the process of learning are closely connected. Radvansky, a researcher for human memory and cognition, explains the connection in his book:

“Memory is a site of storage and enables the retrieval and encoding of information, which is essential for the process of learning. Learning is dependent on memory processes because previously-stored knowledge functions as a framework in which newly learned information can be linked.”

Three stages of human memory processing

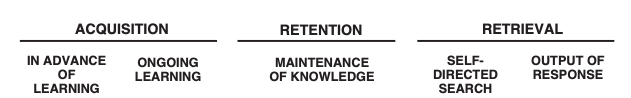

Human memory works in three stages: acquisition, retention, and retrieval. In the acquisition phase, we link new information to existing knowledge; in the retention phase, we store it, and in the retrieval phase, we get information out of our memory.

We use our memory to encode information, retain it, and then access and use our memory to make decisions, interact with others, or solve problems.

Here, we need to understand that the three phases interrelate. Retrieval, the third stage, is cue dependent. This means the more mental links you’re generating during stage one, the acquisition phase, the easier you can access and use your knowledge.

In the words of a research group around Bjork, a renowned human learning and memory researcher:

“To be a sophisticated learner requires understanding that creating durable and flexible access to to-be-learned information is partly a matter of achieving a meaningful encoding of that information and partly a matter of exercising the retrieval process.”

Now, the question is: how can we achieve meaningful encoding and effectively exercise the retrieval process?

Evidence-Based Learning Strategies, Why They Work, And How You Can Apply Them

We’ve established a basic understanding of how our human memory works (acquisition, retention, retrieval). Next, we’ll look at the learning strategies that work best for our brains (elaboration, retrieval, spaced repetition, interleaving, self-testing) and see how we can apply those insights to reading non-fiction books.

The strategies that follow are rooted in research from professors of Psychological & Brain Science around Henry Roediger and Mark McDaniel. Both scientists spent ten years bridging the gap between cognitive psychology and education fields. Harvard University Press published their findings in the book ‘Make It Stick.’

I applied their evidence-based learning techniques for reading. Since I use these techniques, I feel reading indeed is a true investment in knowledge. I can access what I want to remember and use it for writing, podcasting, conversation, or self-improvement.

The strategies presented follow in chronological order and apply to both physical books and e-readers. There are extra supportive capabilities for Kindles that I will explain afterward.

#1 Elaboration

Elaborating means you explain and describe an idea in your own words. Thereby you consciously associate material you want to learn with what you’ve previously learned. In the words of Roediger & McDaniel: “Elaboration is the process of giving new material meaning by expressing it in your own words and connecting it with what you already know.”

Why elaboration works: Elaborative rehearsal encodes information into your long-term memory more effectively. The more details and the stronger you connect new knowledge to what you already know, the better because you’ll be generating more cues. And the more cues they have, the easier you can retrieve your knowledge.

How I apply elaboration: Whenever I read an interesting section, I pause and ask myself about the real-life connection and potential application. The process is invisible, and my inner monologues sound like: “This idea reminds me of…, This insight conflicts with…, I don’t really understand how…, ” etc.

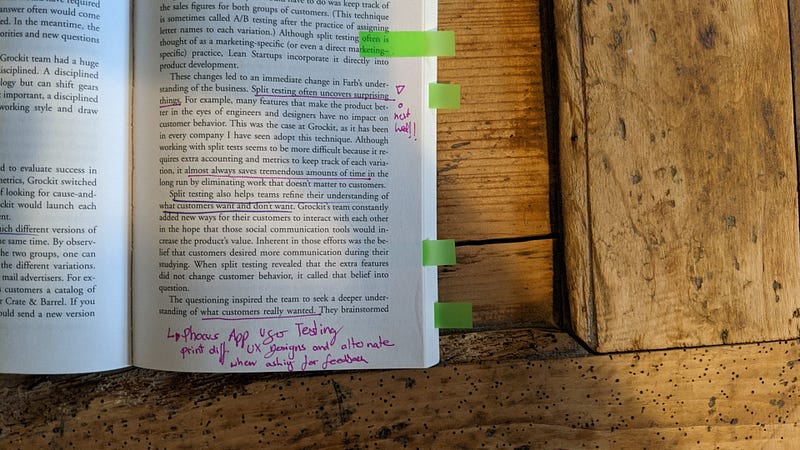

For example, when I learned about A/B testing in ‘The Lean Startup,’ I thought about applying this method to my startup. I added a note on the site stating we should try it in user testing next Wednesday. Thereby the book had an immediate application benefit to my life, and I will always remember how the methodology works.

How you can apply elaboration: Elaborate while you read by asking yourself meta-learning questions like “How does this relate to my life? In which situation will I make use of this knowledge? How does it relate to other insights I have on the topic?”

While pausing and asking yourself these questions, you’re generating important memory cues. If you take some notes, don’t transcribe the author’s words but try to summarize, synthesize, and analyze.

#2 Retrieval

With retrieval, you try to recall something you’ve learned in the past from your memory. While retrieval practice can take many forms — take a test, write an essay, do a multiple-choice test, practice with flashcards — some forms are better than others, as the authors of ‘Make It Stick’ state: “While any kind of retrieval practice generally benefits learning, the implication seems to be that where more cognitive effort is required for retrieval, greater retention results.”

Why retrieval works: The more time has gone since your information consumption, the more difficult time you’ll have to retrieve it. Naturally, a few days after we learn something, forgetting sets in. And that’s why retrieval is so powerful. Retrieval strengthens your memory and interrupts forgetting and, as other researchers replicate, as a learning event, the act of retrieving information is considerably more potent than is an additional study opportunity, particularly in terms of facilitating long-term recall.

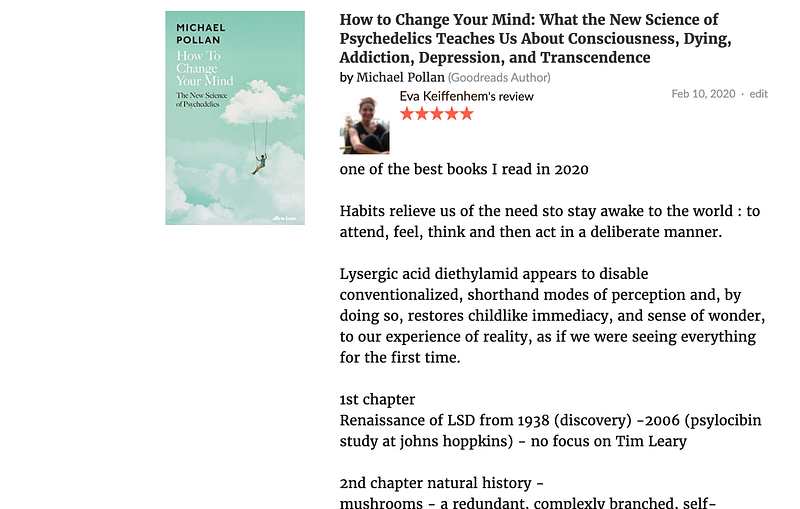

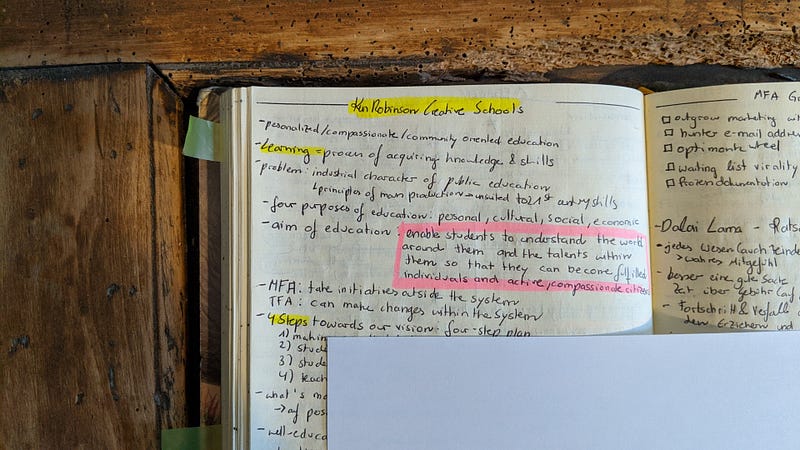

How I apply retrieval: I retrieve a book’s content from my memory by writing a book summary for every book I want to remember. I ask myself questions like: “How would you summarize the book in three sentences? Which concepts do you want to keep in mind or apply? How does the book relate to what you already know?”

I then publish my summaries on Goodreads or write an article about my favorite insights, like here with Ben Horowitz, Elizabeth Gilbert, or Brené Brown.

How you can apply retrieval: You can come up with your own questions or use mine. If you don’t want to publish your summaries in public, you can write a summary into your journal, start a book club, create a private blog, or initiate a WhatsApp group for sharing book summaries.

Whatever you settle for, be careful not to copy/paste the words from the author. If you don’t do the brain work yourself, you’ll skip the learning benefits of retrieval. You want to use your own memory, even if it feels hard. By thinking about the concepts and giving new information your meaning, you’re creating an effective learning experience.

#3 Spaced Repetition

With spaced repetition, you repeat the same piece of information across increasing intervals. The harder it feels to recall the information, the stronger the learning effect. “Spaced practice, which allows some forgetting to occur between sessions, strengthens both the learning and the cues and routes for fast retrieval,” Roediger & McDaniel write.

Why it works: It might sound counterintuitive, but forgetting is essential for learning. Spacing out practice might feel less productive than rereading a text because you’ll realize what you forgot. Your brain has to work harder to retrieve your knowledge, which is a good indicator of effective learning.

So, spaced repetition prevents your brain from forgetting. Research shows repeating the same information ten times over different days is a better way to remember things than repeating the same information twenty times on a single day.

How I apply spaced repetition: After some weeks, I revisit a book and look at the summary questions (see #2). I try to come up with my answer before I look up my actual summary. I can often only remember a fraction of what I wrote and have to look at the rest. I’ll also evaluate whether I’ve applied the knowledge nuggets to my life and, if not, why I didn’t.

The process is quite time-intense, but whenever I feel it’s a timewaster, I remember Ratna Kusnur’s quote on the importance of applying theoretical non-fiction concepts: “Knowledge trapped in books neatly stacked is meaningless and powerless until applied for the betterment of life.”

How you can apply spaced repetition: You can revisit your book summary medium of choice and test yourself on what you remember. What were your action points from the book? Have you applied them? If not, what hindered you?

By testing yourself in varying intervals on your book summaries, you’ll strengthen both learning and cues for fast retrieval. If you read on your Kindle, there’s software to assist you with spaced repetition—more on that after the next two techniques.

#4 Interleaving

In interleaving, you switch practices before completion. So, interleaving means mixing learning with different kinds of approaches, concepts, or viewpoints. By practicing jumping back and forth between different problems, you solidify your understanding of the concepts and promote creativity and flexibility.

Why interleaving works: Alternate working on different problems feels more difficult as it, again, facilitates forgetting. While our intuition tells us completing one topic should be more effective, researchers pointed towards interleaving benefits. Plus, the authors of ‘Make It Stick’ conclude: “If learners spread out their study of a topic, returning to it periodically over time, they remember it better.”

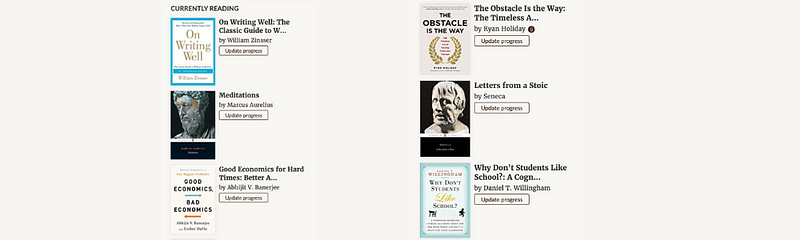

How I apply interleaving: I read different books at the same time. Between my reading start and finish of Harari’s content-dense world history, I read four other books. Mixing my reading with Brown’s vulnerability classic and the memoir of a Holocaust Survivor brought insightful connections between various concepts, similar to what James Clear once meant when he said: “The most useful insights are often found at the intersection of ideas.”

How you can apply interleaving: Your brain can handle reading different books simultaneously, and it’s effective to do so. You can start a new book before you finish the one you’re reading. Starting again into a topic you partly forgot feels difficult first, but as you know by now, that’s the effect you want to achieve.

#5 Self-Testing

While reading often falsely tricks us into perceived mastery, testing shows us whether we truly mastered the subject at hand. Self-testing helps you identify knowledge gaps and brings weak areas to the light. In their book, the scientists conclude: “It’s better to solve a problem than to memorize a solution.”

Why it works: Self-testing helps you overcome the illusion of knowledge. “One of the best habits a learner can instill in herself is regular self-quizzing to recalibrate her understanding of what she does and does not know.” Objective instruments, like testing, or self-testing, help you adjust your sense of what you know and don’t know.

How I apply self-testing: I explain the key lessons from non-fiction books I want to remember to others. Thereby, I test whether I really got the concept. Often, I didn’t. After reading a great book on personal finance, I recorded a podcast episode where I explained how Exchange Traded Funds work.

I reworked my preparation four times until I felt it included everything the listener needs. But instead of feeling frustrated, cognitive science made me realize that identifying knowledge gaps are a desirable and necessary effect for long-term remembering. I keep Mortimer Adler’s words in mind, who wrote: “The person who says he knows what he thinks but cannot express it usually does not know what he thinks.”

How you can apply self-testing: Teaching your lessons learned from a non-fiction book is a great way to test yourself. Before you explain a topic to somebody, you have to combine several mental tasks: filter relevant information, organize this information, and articulate it using your own vocabulary.

When you explain the content from what you’ve read to another person, you’ll identify potential knowledge gaps, can reread the passages you want to double-check, and strengthen your understanding.

Additional Tweaks for Kindle Readers

Most people are e-reading enemies until they truly read their first e-book. I remained an enemy fifteen books in. You can’t dog-ear your favorite pages, scribble your questions in the margins, or elaborate on a concept you just learned. You can’t apply much of what I’d described above.

And while these arguments hold, technology-assisted learning makes most of them irrelevant. Now that I discovered how to use my Kindle as a learning device, I wouldn’t trade it for a paper book anymore. Here are the four steps it takes to enrich your e-reading experience.

1) Highlight everything you want to remember

Based on your new insights into human memory, it won’t surprise you that researchers proved highlighting to be ineffective. It’s passive and doesn’t create memory cues.

And while I join the cannon against highlighting as an ineffective learning tool, we need it to create your learning experience. Use your fingers to highlight any piece of content you find worth remembering. You’ll next understand why.

2) Cut down your highlights in your browser

After you finished reading the book, you want to reduce your highlights to the essential part. Visit your Kindle Notes page to find a list of all your highlights. Using your desktop browser is faster and more convenient than editing your highlights on your e-reading device.

Now, browse through your highlights, delete what you no longer need, and add notes to the ones you really like. By adding notes to the highlights, you’ll connect the new information to your existing knowledge. You might recognize this tactic as an effective learning strategy you learned earlier: elaborative rehearsal (see #1 elaboration).

3) Use software to practice spaced repetition

This part is the main reason for e-books beating printed books. While you can do all of the above with a little extra time on your physical books, there’s no way to systemize your repetition praxis. As you know, spaced repetition (see #3) helps you prevent your brain from forgetting and will strengthen your memory.

Readwise is the best software to combine spaced repetition with your e-books. It’s an online service that connects to your Kindle account and imports all your Kindle highlights. Then, it creates flashcards of your highlights and allows you to export your highlights to your favorite note-taking app.

Common Learning Myths Debunked

While reading and studying evidence-based learning techniques I also came across some things I wrongly believed to be true.

#1 Our brain’s capacity is limited

This is simply untrue. As the researchers write in this paper: “We need to understand, too, that our capacity for storing to-be-learned information or procedures is essentially unlimited. In fact, storing information in human memory appears to create capacity — that is, opportunities for additional linkages and storage — rather than use it up.” You increase your brain’s capacity for learning.

#2 Effective learning should feel easy

We think learning works best when it feels productive. That’s why we continue to use ineffective techniques like rereading or highlighting. But learning works best when it feels hard, or as the authors of ‘Make It Stick’ write: “Learning that’s easy is like writing in sand, here today and gone tomorrow.”

While techniques like retrieval, spacing, and interleaving can feel hard and appear as if the learning rate would be very slow, the opposite is true. As the researchers write in this paper: “Because they often enhance long-term retention and transfer of to-be-learned information and procedures, they have been labeled desirable difficulties, but they nonetheless can create a sense of difficulty and slow progress for the learner.”

In Conclusion

While these techniques stem from evidence-based learning strategies, their application is my preference. I developed and adjusted these strategies over two years, and they’re still a work in progress.

Try all of them but don’t force yourself through anything that doesn’t feel right for you. I encourage you to do your own research, add further techniques, and skip what doesn’t serve you. Instead of feeling discouraged by all the ideas about how you can improve your learning experience, enjoy experimenting at your own pace. Keep the steps that work for you and screw the rest.

If you’re unsure where to begin, or you’re overwhelmed by all the application strategies, I suggest you start with book summaries first. Writing down what you want to remember makes you think about and rephrase what you just learned.

You can then use it for future spaced repetition (#3) or as a reference guide if you want to teach your insights to somebody (#4). And to write the summary, you will soon realize it’s helpful to elaborate (#1) while reading. Doing it with several books simultaneously (#2) can be a level up once you feel comfortable with the implemented routines.

No matter which strategies you use, applying evidence-based learning strategies will pay off. It’s not a quick win and takes time and patience, but you’ll ultimately reap the benefits.

“In the case of good books, the point is not to see how many of them you can get through, but rather how many can get through to you.”