Your guide to fleeting literature and permanent notes using Roam

Taking smart notes is the fast-track to improve your productivity and creativity. Yet, most note-taking systems are ineffective.

Niklas Luhmann, a notable sociologist, was living proof for a system that is effective. During his life, he wrote 70 books and 500 scholarly articles. He attributes his success to a note-taking system called the Zettelkasten, which is the German word for slip box (Luhmann’s system was done on index cards or “slips,” stored in boxes, and later digitized).

I read a book and 50 articles a week. But I struggled to manage the input and my ideas for creative output. While writing an article I often remembered I read something related. But whenever I went searching in my Trello idea board, Bullet Journals, or Notion folders I struggled to find what I was looking for.

I’ve been using his method for two months, and I can already see how it’s improving my reading and thinking. By using the three note-taking levels, I not only generate more ideas but also discover new ones I hadn’t thought about. The creative workflow for my articles, podcasts, and clients finally feels efficient.

Thanks to the system I write and create faster; for instance, a research-based 1800-word article used to take me four hours — with Zettelkasten, it takes me two. Whenever I prepared a speech I spent days going through related journal entries and books. Now I open topic-related Roam pages and have all the ideas in one place. I even stumble upon thoughts I didn’t consider in the first place.

To implement the system, I watched and read tutorials, studied Sönke Ahren’s classic, researched coaches, and hired one. And while much of the existing content is great, it fails to distinguish between different note types.

This is the tutorial I wish I’d had when setting up my slip box. I skipped the technical how to get started in Roam advice (because there are great tutorials) and instead focused on what’s made my Zettelkasten such a huge force for changing my knowledge management.

Level 1: Fleeting Notes

Fleeting notes are ideas that pop into your mind as you go through your day. They can be really short, just like one word. You don’t need to organize them. They just serve as reminders of your thinking.

These notes have no value except as stepping stones for turning literature notes into permanent notes. You discard the fleeting notes once you transformed them into permanent notes (more on that in level 3).

The only important thing here is to have an easy way to capture them. I use a simple notebook, but a preinstalled notes app works as well.

Level 2: Literature Notes

You capture literature notes from the content you consume. It’s your bullet-point summary from other people’s ideas. I create these notes for all books, podcasts, articles, or videos I find valuable.

How to take proper literature notes

There are three rules for literature notes: make them brief, use your own words, and note bibliographic references.

Sönke Ahrens adds another rule. He recommends being extremely selective in what you capture. I’m not. For deciding what I convert into literature notes, I ask myself:

- What is interesting about this?

- What’s so relevant it’s worth noting down?

By transforming consumed content into literature notes, you’re using one of the most effective learning strategies. When you elaborate, you rephrase new information in your own words and connect it to existing knowledge. You’ll make it more likely to remember what you read.

Researchers from the University of Otago, New Zealand, showed the more you write down, the more you can recall the information later. So don’t try to keep the notes too short — be generous in the way you elaborate and find the length that feels good for you.

How to create meaningful references

In traditional note-taking settings, the idea is to file new information based on the context you found it. I kept a Notion page for notes on productivity, another one for notes on writing, and so on.

But with Zettelkasten, the categorization is more efficient. A note is only as useful as its context. A note’s true value unfolds in its network of connections and relationships to others.

You don’t have to use your brain anymore to find separate ideas from different books related to each other. In a Zettelkasten, you don’t file notes in the context you found them but in the context in which you want to discover them.

“Making good cross-references is a matter of serious thinking and a crucial part of the development of thoughts.”

Here are two questions to ask yourself when you create references for your literature notes. Answering them will help you make good cross-references:

- In which circumstance do I want to find this note?

- When and how will I use this idea?

Thereby, you assign keywords by thinking about topics you’re working on, not by looking at the note in isolation. I cross-reference my literature notes by using #tags in my Roam database.

Level 3: Permanent Notes

Permanent notes are the real value-adders. You create them by looking through your fleeting and literature notes. Ideally, you create them once a day.

Both Sönke Ahren and Andy Matuschak say a knowledge worker’s productivity should be measured by the number of permanent (or evergreen) notes they write in a day.

“If you had to set one metric to use as a leading indicator for yourself as a knowledge worker, the best I know might be the number of Evergreen notes written per day.”

How to create permanent notes

In the beginning, I felt confused about permanent notes: When should you write one? Which ideas are worthy enough? And what length should they have?

As a rule of thumb, I now create permanent notes about every topic I’m curious about or working on. When you’re in doubt, ask yourself whether you’re curious to explore your idea further.

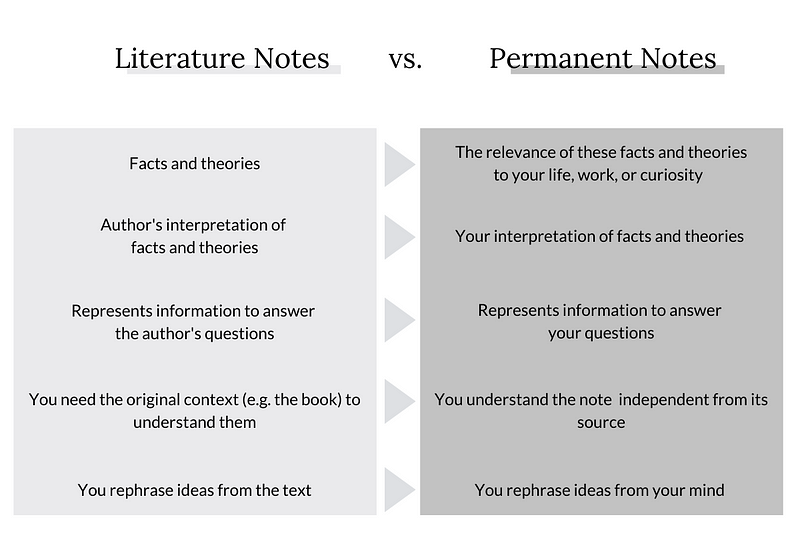

When you create permanent notes, you think for yourself. In contrast to literature notes, you don’t summarize somebody else’s thoughts. You don’t just copy ideas but develop, remix, and contradict them. You create arguments and discussions.

While your literature notes are bullets, your permanent notes are written prose. A reader of your permanent note should understand it without reading the source that led to your idea.

Your future self should understand every permanent note in its own context and directly use them for content creation.

Each permanent note contains only one single idea. When you create them you don’t write a full article. You write ideas. That’s how they become reusable.

“Write exactly one note for each idea and write as if you were writing for someone else. Use full sentences, disclose your sources, make references, and try to be as precise, clear, and brief as possible. “

Once you write an article or a book about a specific topic, you don’t start with a blank page. Instead, you search for permanent notes relevant to your topic.

Since I used the Zettelkasten, my writing time almost halved. Before, it took me around three and a half hours to write a research-based 1500-word article. With this note-taking system, it takes me two.

The reason for the time reduction is the built-in idea suggestion mechanism. Whenever I write about a topic, I stumble upon related thoughts. All I have to do is connect my permanent notes into coherent texts.

How to connect permanent notes

The Zettelkasten becomes more useful as it grows because you discover related ideas you hadn’t thought of in the first place. But to find the right ideas at the right time, you need to do proper housekeeping.

“Notes are only as vaulable as the note and reference networks they are embedded in.”

When recording a new permanent note, always think about linking that note to existing ideas and concepts. To do so, ask yourself questions like:

- How does this idea fit your existing knowledge?

- Does it correct, challenge, support, upgrade, or contradict what you already noted?

- How can you use this idea to explain Y, and what does it mean in the context of Z?

The relationship between literature and permanent notes

When I first started, I was confused about whether to create permanent notes for each literature note. And, if that’s the case, what to do if I don’t have any new ideas I can add to the literature note?

I create permanent notes by going through my literature and fleeting notes and searching for ideas, principles, or concepts that I want to explore further. I let curiosity guide me. Sometimes my idea is truly original. Other times it’s just a reference to the original source added with a personal anecdote.

Permanent notes are no holy grail — but a work in progress. Don’t be afraid to write them. You can change and update them whenever you want: what permanent really means is that they’re permanently useful to you.

Final Thoughts

Creating a personal knowledge database can feel difficult. First, the many options and tutorials confuse you. Then, building a system slows down your consumption speed.

But if you’re a knowledge worker or content creator and some of this sparked your curiosity, I’d urge you to follow your impulse.

A Zettelkasten can work as an idea-generation machine. You discover related ideas that you hadn’t thought of in the first place. As your notes grow, you likely start seeing puzzle pieces for the bigger picture. This picture can serve as the basis of your original work.

May this article support you in taking your note-writing system to the next level.