And how I use a Roamkasten to work with mine.

With 24 hours a day and limited days before you die, you’re facing a trade-off between how you spend and not spend your time.

Nobel Prize-winning physicist Richard Feynman was well aware of this dichotomy, and he developed a framework that helped him navigate through life.

If you ever wondered whether you’re using your time for the right things, this timeless idea will help you direct your attention to what matters most.

Richard Feynman’s Mental Framework

While most people find problems inconvenient, Feynman took a fresh approach. Through his lens, problems can give your life meaning and purpose. He once wrote:

“My approach to problem-solving is to carry around a dozen interesting problems, and a dozen interesting solutions to unrelated problems, and eventually, I’ll be able to make connections. […].

You have to keep a dozen of your favorite problems constantly present in your mind, although by and large they will lay in a dormant state.”

What Feynman intuitively described, learning scientists now call the diffuse modes. Without actively thinking, your subconsciousness works on problems.

It not only helped Feynman become a highly respected physicist but also other world-class performers, such as Stephen King.

King says he found the best ideas for his novels during diffuse mode thinking: “These were all situations which occurred to me while showering, while driving, while taking my daily walk and which I eventually turned into books. [..] It’s that sudden flash of insight when you see how everything connects.”

Once you know your favorite problems, you don’t need to work on them constantly. Your mind will look for answers while you’re focusing on something else.

In essence, your favorite problems are questions that help you get into an explorer mindset. When you read through other people’s ideas, you’ll unconsciously make connections to your favorite problems. Day by day, you’ll make progress on finding solutions.

“Every time you hear a new trick or a new result, test it against each of your twelve problems to see whether it helps. Every once in a while there will be a hit, and people will say, ‘How did he do it? He must be a genius!’”

— Richard Feynman

How to Find Your Favorite Problems

Your favorite problems can be anything — related to your work life, scientific questions, your love life, your health, wealth, or humanity as a whole.

The only important thing is to settle on problems you can contribute to. In a letter from 1966, Feynman wrote to his former student Koichi Manom:

“The worthwhile problems are the ones you can really solve or help solve, the ones you can really contribute something to. […] No problem is too small or too trivial if we can really do something about it.”

To find twelve worthwhile problems for your life, consider the following questions:

- What are you curious about?

- What have you always pursued?

- What puzzles you about life and society?

- Which problems you can’t stop thinking about?

Most of your favorite problems won’t have a single solution. The goal is not to be done with them. Your questions will stay with you or evolve, sometimes for years or even decades.

How I Work With My 12 Favorite Problems

To serve as guiding principles for your life, you’ll want to revisit your questions regularly.

I work with my problems by using a Zettelkasten with Roam. The Zettelkasten was invented by socioligist Niklas Luhmann. Thanks to the method, he published 70 books and 500 scholarly articles.

I’ve been using a digitized version of Luhmann’s system for four months. I can already see how it’s improving my writing, thinking and helping me find answers to my 12 favorite problems.

Understanding and implementing the system takes about five to ten hours, but here’s the quintessence of Zettelkasten’s notes hierarchy:

- Fleeting Notes

Fleeting notes are ideas that pop into your mind as you go through your day. They can be really short, just like one word. You don’t need to organize them. - Literature Notes:

You capture literature notes from the content you consume. It’s your bullet-point summary from other people’s ideas. I create these notes for all books, podcasts, articles, or videos I find valuable. - Permanent Notes:

When you create permanent notes, you think for yourself. In contrast to literature notes, you don’t summarize somebody else’s thoughts. You don’t just copy ideas but develop, remix, and contradict them. You create arguments and discussions.

My 12 favorite problems serve as a filter for my permanent notes. Whenever I develop my opinion, I think about how it relates to my favorite problems.

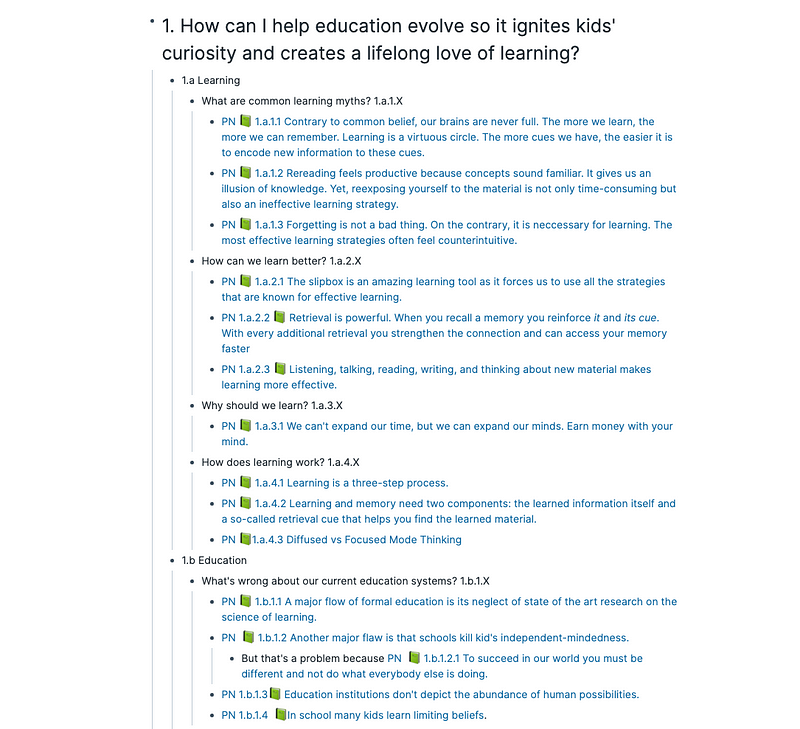

Here’s a snapshot of my current permanent notes page on my first favorite problem — How can I help education evolve so it ignites kid’s curiosity and creates a lifelong love of learning?

By using your favorite problems as guiding questions for your permanent notes, you will start to get answers. Plus, you’ll revisit your questions regularly.

In Conclusion

Writing your interests as a dozen questions will help you clarify what you’re truly after and making better decisions.

By keeping a list of problems, you can decide what you want to read, watch, or listen to. Feynman’s framework can work as a system of filters and turn consumption into contribution.

All you need to do is write down your 12 favorite problems and keep them in the back of your head, e.g., through integrating them in your Zettelkasten.

As you capture information to find answers to your favorite problems, you will start to see patterns of interest and find more meaning in life.